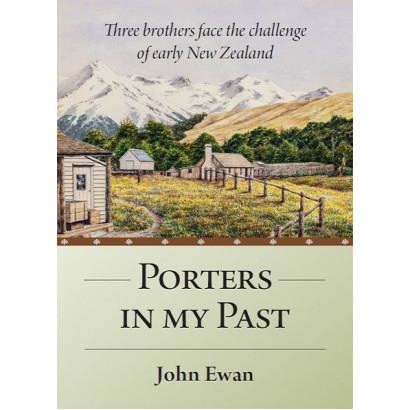

Porters in My Past

Immediate Download

Download this title immediately after purchase, and start reading straight away!

View Our Latest Ebooks

Explore our latest ebooks, catering to a wide range of reading tastes.

From: Porters in My Past, by John Ewan

Chapter 2: David the Surveyor

The death of Mr. David Porter, Draughtsman in the Wellington Lands and Survey Office, took place on the 14th April, 1901. His record of service extended from June, 1853, commencing under the General Government, merging into that of the Provincial Government, and finally under this Department. He had a record for longest service as a District Surveyor, in which capacity he rendered excellent work in the early days of the colony, and was universally respected and esteemed by all who had the good fortune to claim his acquaintance or friendship.

Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives,

1902 Session I, C-01 Page I, Department of

Lands and Survey Annual Report

WHEN DAVID PORTER DIED ON 14 APRIL 1901, news of his death was telegraphed around the country. Several newspapers published an item saying he was of the Department of Lands and Survey and had arrived in New Zealand on the Cressy. To have news of one’s death printed in the local paper is understandable, but why did so many other papers pick up that item and print it? There must have been some reason to consider him newsworthy.

Far from the wind-swept station in the Rakaia where David Porter worked as a cadet. His employer Mark Stoddart brought this cottage to Diamond Harbour, where it became a local landmark for many years. Photo: John Ewan.

Furthermore, the Cressy had arrived in Christchurch more than half a century earlier, and David appears to have spent most of his life in the North Island. So why was the item also run in southern papers? And, what was the reason for his moving to Wanganui and then to Wellington?

Other puzzles involving David also turned up. Given the difficulty of travel in those times, I was interested to find a reference to Ernest Charles Wilmot Porter, described as the son of Mr David Porter of Wanganui, being made a Captain in the Queenstown Rifles Volunteer Corp. Why would a young man, educated at Wanganui Collegiate, turn up as a soldier (albeit voluntary) in Queenstown? Maybe Ernest could somehow provide the key to why David Porter had moved north.

A visit to the Queenstown Library produced the suggestion that Ernest may have gone there to seek his fortune at the goldfields. (There had been a huge discovery of gold at the Shotover.) This theory quickly evaporated when we discovered in The Cyclopedia of New Zealand, dated 1906, that Captain Ernest was in Queenstown because he had been appointed manager of the Bank of New Zealand. The appointment came much later than the gold rush, too. Ernest took up his appointment in 1899, long after the time when Queenstown was called Canvastown and the bank operated from a tent on the site that was to become Eichardt’s Hotel.

Later I discovered that Ernest did have a connection with gold. As manager of the bank at Arrow (now Arrowtown) before his Queenstown appointment, he was required to collect gold from the bank’s agents. Sometimes he went by horseback to places such as Cardrona, with a revolver as his sole means of defence. There would have been some degree of risk, considering the distances he travelled. His son Lance recalled: “He had many a lonely ride over the Crown Range, but it did not seem to worry him.” (Unpublished memoir by P L Porter)

Intriguing though the story of banking in the early times was, discovering David Porter by tracking down his son Ernest would have to wait for another time.

David Porter’s arrival in New Zealand may not have been a matter of such great moment as his death. However, the arrival of the Cressy was indeed news. Cressy has remained stamped in the province’s collective memory as one of the First Ships to arrive at Lyttelton with the Canterbury settlers. It is somewhat curious that there should be a newspaper up and running to report the event barely two weeks later. However, this may be explained by Cressy being the last of the four to arrive. But more to the point, there was European settlement in Canterbury before the so-called ‘first four ships’.

In its very first issue, the Lyttelton Times describes the voyage of the Cressy in a lengthy article based on interviews with new arrivals. It talks of the sadness as the ship, a 720 tonne barque, set sail from Gravesend. Three days later it reached Plymouth to collect passengers before setting out for southern waters via the Cape of Good Hope. Due to problems with a foremast while rounding South Africa, Cressy arrived in New Zealand in fourth place among the first four ships, putting down anchor on 27 December 1850. Crew and passengers had missed reaching their destination in time for Christmas, but in those days the important thing was to have arrived at all. One hundred and fifty-five made the trip.

Altogether, some 900 settlers travelled on those first four ships, described as “first class passenger ships” in an advertisement in The Times 1859. Fares were £42 for chief cabin, £25 for fore cabin, and £15 for steerage. “Rate of passage,” the advertisement declared, included “provisions, medicine and medical comforts.”

I have some pride in being related to the emigrants on those first four ships. But it also feels funny not to have known for over 60 years that my own great grandfather was one of them. And of course it is worth remembering, as noted above, that they were not the first European settlers in Canterbury. Among those already there were the passengers from the French ship who established two villages on Banks Peninsula in 1840. There had also been attempts to settle on the Canterbury plains from the early 1840s. The widely known Deans family was there from 1843.

The exact number of passengers who arrived on the first four ships of the Canterbury pilgrims is open to question. Various passenger lists do not tally, and there are further discrepancies due to births and deaths en route.

It would be another 20 years after the pilgrims arrived before the flow of immigrants to New Zealand really gathered momentum. However, these four ships plus earlier settlements in the other main centres were the start. Between 1850 and 1853, 3549 people arrived in Canterbury, according to The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Few of these voyages were ever easy, as evidenced by David Hastings.1 He has written graphically on the harshness of life on these long journeys, particularly for those below decks in steerage.

The four ships that set sail on 20 August 1850 – Sir George Seymour, Charlotte Jane, Randolph and Cressy – were given a big send-off. Functions included a breakfast banquet with the band of the Coldstream Guards in attendance. Lord George Lyttelton, former Under Secretary for the Colonies, proposed several toasts.

According to the Lyttelton Times report, the Cressy had a comparatively uneventful trip. One passenger went mad; another fell overboard but was rescued. There was trouble with a mast. David Porter had a cabin which would have provided at best a degree of comfort. And interestingly, the passenger list included the name Dobson, which figured later in the naming and construction of Arthur’s Pass.

The new arrivals were certainly not arriving at a new England on the other side of the world. Dobson later described the arrival, quoted by P L Porter in his memoirs: “In the small settlement there were barracks for the Pilgrims, and some rough shelters made of undressed timber, and some tents covered with tarpaulins and canvas. The only road was a rough track, known as the Bridle Path, about six feet wide, on a very steep gradient, leading over the hills into the Heathcote Valley.”

Why did a young man of 22 come out alone to New Zealand in the first Pace? It’s a hard question to answer. The family notes (incorrectly, it would seem) said there were three brothers at Castle Hill Station. They all came in separate ships. That bit was true. Was this an insurance policy against a disaster at sea killing them all off at once if they had sailed together?

Given the then speed of communications and the timing of the arrivals, it is unlikely one brother could have sent back glowing reports that encouraged the others to follow. There would simply not have been the time.

And given that David was in the chief cabin class, one senses the influence of a sponsoring parent. Could Father have seen the end of the family fortune and set out to provide for his sons in a new land? There is another clue in an article entitled “Victorian Life at Hawkshead” by Sonia Addis Smith on the website www.Brookman.com. She says Hawkshead was the family home at the time and there were references to dampness. Maybe the other side of the world seemed a healthier place.

The other question that begged an answer was: What did David do once he landed in Christchurch? It was not until 1858 that the Porters took up the Castle Hill lease, eight years after the Cressy had anchored.

In 1851 David was living with brother Joshua in Christchurch, judging by a comment in Dr Gundry’s Diary, Part II: Commencing Practice in Christchurch June-October 1851.2 On 31 August that year Gundry wrote he called to see Joshua. “Truly their house presents a picture of a bachelor’s retreat in the Colonies. I never saw such a muddle – such a scene of disorder and discomfort.”

However, his comments did not stop him from leaving his watch for David to repair a few weeks later. The following day (1 September) “Mr Porter, jr [David] called this morning with my watch – it goes again now.”

It is also known that in 1852 his name appeared on the jury list for 13 August. That is nearly two years after he arrived in New Zealand. His address is given as River Avon and his occupation as civil engineer.

But David may have already left town by then. An item entitled “Memorial of Settlers of Wellington and neighbouring districts” appeared in April 1851. The name of David Porter, settler, was among the many who signed this general disapproval of the NZ Company addressed to Governor Sir George Grey3. Given the NZ Company was not active in Christchurch, it would appear either that David was already in Wellington, or that there was another David Porter!

There is one other clue. In The Reed dictionary of New Zealand place names,4 an entry for Porters Pass says that the Porter brothers lived for some years in a whare near the banks of the Avon and close to Cathedral Square. The home was described as a “Van Diemen’s Land paling whare and a familiar landmark”.

Apart from these few clues, and a reference to his going with brother Joshua to Dr Gundry to sell tickets for a ball, David’s time in Christchurch appears to have passed unrecorded.

However, it is also known David worked for a time on the 20,000 acre Rakaia Terrace Station – at least until 1853, when the station was purchased by John Hall, later to be knighted for services to politics. David’s employer at the station was Mark Stoddart who had arrived from Australia. A wealthy Scot and son of an admiral, Stoddart sold his station in Victoria and then chartered a vessel to take him to New Zealand.

Stoddart was known as a Shagroon, one of that bunch of Australian ‘squatters’ who came to New Zealand in the mid-nineteenth century to make a fresh start.

There is an interesting comment in the Lyttelton Times.5 “We are deeply concerned to find that he [Stoddart] has pitched his camp in a gorge from whence, it would seem, all the winds in New Zealand proceed.” The comment concludes that “he appears to have surrounded himself with many of the requirements of civilisation”.

But Stoddart’s stay in the Rakaia was short-lived. He also owned property at Diamond Harbour and left the Rakaia run after only two years. David Porter, a cadet on the station, appears to have left the area at the same time. The term ‘cadet’ was widely used in those days. It described people who lived in as part of a farmer’s family and paid for the privilege. However, they were also expected to work as shepherds without pay. If the owning family moved, it would therefore have been a matter of consequence that David had to leave the station.

The cadet theory was that it trained young men to become station managers, but the scheme was largely unsuccessful. Cadets paid for the so-called privilege of staying on a farm. There was no incentive for them to exert themselves: if the cadet got sacked, the farmer would be left out of pocket by the departure of free labour.

Stoddart moved on to jointly own Glenmark Station, but his interests clearly lay in the city. He lived at Diamond Harbour in a cottage that had been shipped from Australia. The cottage became a local landmark.

While Stoddart received some recognition as a poet, his daughter Margaret Olrog Stoddart became a prominent painter and her influence was acknowledged by Rita Angus.

After leaving the Rakaia, David became district surveyor for the Wellington Provincial Government. He married Anna Maria Powell in 1855 at Christ Church Wanganui. So we know he was in Wanganui three years before the Porters took up the first two runs at Castle Hill.

So was my great grandfather David involved in any manner at Castle Hill? Was he an absentee part-owner? When talking about the great surveyor-explorers of New Zealand in The Penguin History of New Zealand, historian Michael King6 mentions Colenso, Shortland, Brunner and Heaphy amongst others. The name Porter is not among them.

Was he just another of the early settlers who fitted Philip Temple’s description of “…too many speculators, too few labourers and not much from which to earn an income”?7 Yet his death was noted in so many newspapers.

Perhaps it’s time to see what is known about the other two brothers.

NOTES

1 David Hastings Over the Mountains of the Sea (Auckland University Press 2006)

2 Dr Gundry’s Diary, Part II: Commencing Practice in Christchurch June–October 1851, The Nag’s Head Press, Christchurch, 1983

3 NZ Spectator & Cook Strait Guardian, 3 April 1851

4 A W Reed, [Peter Dowling, ed.] The Reed dictionary of New Zealand place names (Reed) 1975

5 Lyttelton Times, 8 May 1852

6 Michael King The Penguin History of New Zealand (Penguin)

7 Philip Temple Presenting New Zealand (New Holland 2001)