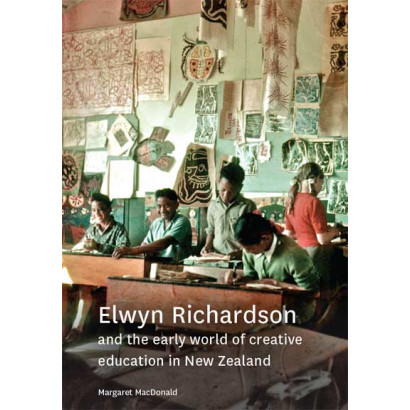

Elwyn Richardson and the Early World of Creative Education in NZ

Immediate Download

Download this title immediately after purchase, and start reading straight away!

View Our Latest Ebooks

Explore our latest ebooks, catering to a wide range of reading tastes.

From a one-roomed school in the remote Far North of New Zealand, Elwyn Richardson became a radical and internationally-renowned teacher. This is his story and it is as inspirational and timely for educators and policy makers as ever.

This book explores the man and the influence of the innovative pedagogy he developed at Oruaiti School from 1949 to 1962. Central to his philosophy was his use of the natural environment to create an integrated programme of art and science.

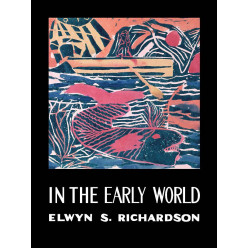

Described as an ‘educational saboteur’ by poet James K. Baxter, Richardson valued curiosity and turned to children’s lives and their immediate surroundings to shape his curriculum. Learning was often organised in themes and students worked together on real problems drawn from the local community. The record of his teaching at Oruaiti, In the Early World, first published by NZCER in 1964, was widely used in teacher education in New Zealand and the United States

From: Elwyn Richardson and the Early World of Creative Education in NZ, by Margaret MacDonald

Chapter 1: Introduction

The one-roomed school in rural Northland, New Zealand, is filled with the sound of 26 children, from 5 to 12 years old, talking as they work. Mobiles hang from the rafters and the walls are covered in vivid paintings, linocuts and wood-block prints. A small electric kiln occupies the corner of the room, and a cluster of pots and clay masks sit drying on a shelf nearby. Their teacher, Elwyn Richardson, a 28-year-old with a passion for palaeontology, moves from child to child as they discuss their work.

On the teacher’s desk at the front of the room sits a large professional microscope. The children take turns placing objects beneath the lens: a leaf, a wing, the bony leg of a wasp. As they look through the lens they enter a magical world. And as each child turns away, filled with wonder, they know now that things are different out there, and they begin to imagine what those things are like or could be. They are encouraged by their teacher to record their observations through written descriptions, drawing or sculpture, and to think of other ways to make use of what they have discovered.

The paddocks beyond the classroom have been cleared of gorse and scrub and are now run with cattle. Beyond them, the hills of the Maungataniwha Range define the skyline and feed the Oruaiti River, which winds its way along the valley floor and comes within a stone’s throw of the classroom.

Elwyn Richardson was drawn to Northland because he, too, was captivated by what he had seen through the lens of a microscope. A childhood immersed in nature on Waiheke Island, and 3 years of chemistry, botany and geology at the University of Auckland, had sparked a keen interest in the study of native fossils and fauna. (For financial reasons he had to leave university before completing his degree—a situation that troubled him throughout his life.) The remote, sole-charge posting at Oruaiti School offered him the opportunity to follow his interest in molluscan palaeontology, but also to construct his own pedagogy, curriculum and assessment, away from the immediate gaze of school inspectors and colleagues. His two children Anna and Stuart attended the school, and their mother Margaret, Richardson’s first wife, was active in the local community.

Over the next 13 years, from 1949 to 1962, Richardson developed his own philosophy of education. He discarded the official syllabus and turned instead to the children’s lives and immediate environment for the basis of his curriculum. Using the children’s natural curiosity and interest, he taught his pupils how to look closely at the world around them, and to observe and record their new discoveries and their own responses to them. From here he developed a dynamic programme that was anchored in the children’s surroundings and lives. Through this environmental study the children learned the basis of scientific method and brought these skills to bear on studies that spanned different subjects. It was a revolt away from science as a separate subject, and towards an integrated programme of arts and science. Instead of science workbooks to mark, there were experimental results on a chart, creatures observed at various stations in the classroom, and paintings, poems, stories and plays about what the children had discovered.

Richardson used the children’s interests as inspiration for more formal lessons in maths, social studies, geography, history and English. A child wondering aloud at the full stop after the ‘Mr.’ on an envelope, for instance, led to a week-long ethnographic study of errors on personal and business envelopes. The work focused on grammar, formal and informal writing, but also became a social study of their community as they analysed envelopes, and researched and drew conclusions about the writers, their occupations and their errors.

Mustering and fishing—activities in which many of the children participated—provided the basis for the study of maps and geography. Number work was structured around difficulties posed by deep-water fishing, with the effects of current, depth and wind all providing problems that were worked out and recorded by the children. Language work and painting frequently evolved from these lessons. Learning was often thematically based, and group studies emerged out of real problems in the local community, such as an infestation of porina moth on cattle-grazing land, the spread of gorse on farms, or the salinity levels measured by the children in the river where they swam. It was a school without walls.

Richardson and his school gradually became an international symbol of ‘progressive’ education—a term he himself disliked—with a particular focus on arts and crafts. His book, In The Early World (published in 1964 by the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER)), a record of his experience at Oruaiti School, was used in teacher education programmes in New Zealand and the United States, especially in the area of developing reading and writing skills in young children.

Significantly, publication of In The Early World coincided with a cooling of enthusiasm for learning through the arts and Richardson found himself unable to publish anything further. Clarence Beeby, Director of Education from 1940 to 1960, had been supportive of Richardson’s work at Oruaiti but had left to accept a position as New Zealand Ambassador to France for UNESCO in 1960. His vague promise that Richardson’s book might result in the award of a degree did not come to anything.

Difficulties with inspectors in the early years of the Oruaiti ‘experiment’ continued to rankle Richardson and were compounded, over time, by personal and professional tensions that escalated between him and educational administrators. His self-published works immediately after In The Early World reflect his sense of isolation in his last few years at Oruaiti, and they are laced with barbed references to educational administrators— “little grey men”, as he called them. For the Pantheon edition of In The Early World, published in the United States in 1969, Richardson asked the NZCER editor, John Watson, to change the original inscription to read:

This book is dedicated to the little grey bastards of the department without whose meddling and pimping ways this work would never have been started.

In the end Richardson decided against this dedication, but it is clear that at times he felt professionally abandoned, misunderstood and manipulated, even though in terms of practical support he was generally well treated.

Elwyn Richardson might be seen as both a rebel and a reformer in his relationship with the philosophy of the day. He was both respected and feared by the school inspectors, whom he challenged with his progressive philosophy and innovative methods. He positioned himself as an outsider, yet in many ways he was the unconscious beneficiary both of other people’s ideas and of a great transformation in the role of art and craft in the New Zealand primary school. Richardson’s work at Oruaiti School has been almost exclusively interpreted as a unique experiment in art and craft education, but the art and craft emphasis at Oruaiti arose directly out of a scientific foundation that was shaped more by Richardson’s interest in environmental study than by the dominant ideas about child art at the time.

Although art and craft were not the primary focus of Richardson’s educational philosophy, this is the area in which much of the radical reform in thinking about children’s education took place over this period. Theories about natural expression, the importance of play, and allowing a child’s mind to develop without the imposition of adult perspectives are more naturally related to art and craft, rather than to science and mathematics. That is why this account of his work is also a history of the social and intellectual currents in the development of art and craft teaching in New Zealand primary education in the first half of the 20th century. Ideas on the pedagogy of art and craft provide a lens through which to view the kind of educational developments that set the scene for the Oruaiti experiment.

It is precisely because the historical institutional context was hospitable to innovation in creative education that Richardson’s generally negative comments about the Department of Education of his day, and his fraught experience of doing something different in New Zealand education, are worth closer examination. The intersection of history and biography creates an opportunity to better understand both the system and the individual. It is overly simplistic to see Richardson’s generally negative comments about his interactions with the Department of Education as some sort of necessary anti-establishment stance that was conducive to rebellion, as has been suggested by some. Instead, we can learn from asking what these tensions reveal about the nature of educational reform in New Zealand and internationally.

And what do they reveal about Elwyn Richardson? To examine this question is to explore the local and the particular—the experience of one radical New Zealand educationalist and the space the New Zealand educational establishment provided for him to do something different. Implicit in this question are the broader questions that big-picture visions of education continue to return to—vital questions about the relationship between education and society, education and the learner, education and knowledge; between aims intended and aims achieved.

The issues facing Richardson when he first began his experiment were complex. Apart from 2 years’ probationary training working at Puni School, near Pukekohe, he was, in his early 20s, very much a beginning teacher. During his time at Oruaiti School he won the support of parents from very different religious and cultural backgrounds, and developed ways of working in a bicultural classroom with children who ranged from 4 to 12 years old, many of whom had English as a second language. He incorporated te reo Māori (the Māori language) into his classroom, shunned corporal punishment, and created a democratic learning environment in which the cultural diversity of the community and the children was both respected and celebrated. It is worth noting here that the separate Native School system for Māori children in New Zealand was not disbanded until 1969, corporal punishment in state schools did not become illegal until 1990, and it is only in recent years that teacher-training colleges have incorporated te reo Māori into their courses. In 1949 Richardson was, indeed, radical and in many respects educationally ahead of his time.

His belief that all real learning must be anchored in personal experience provided the foundation for his developmental approach to education. Central to this was his theory of ‘integration’—a personalised process in the arts whereby children move from one expressive medium to another, across all subject areas. His concept of integration was based on the belief that paint, clay, language, dance and drama offer different possibilities for expression, and that often a child is not able to express all s/he has to say about a subject in a single medium. In this way, a painting about a pūkeko might lead to a linocut, which might lead to a poem, a dance or a play. In each, the theme remains the same, but the motivation to express something new or different is brought to fruition in the new medium, or in the reworking of the same medium. Richardson’s theory of integration was informed by his conception of artistic ability as a universal human attribute, his well-developed ideas about the nature of artistic development in children, and a firm belief in the learning potential of every child.

As well as fostering the role of the imagination in intellectual work, Richardson developed a range of pedagogical strategies to help children internalise discriminating criteria for their expressive work—in all media. The children’s creative work was discussed and evaluated by them at a weekly class meeting. Run by the children, these assessment sessions led to the growth of shared values and a class culture akin to a community of artists working together. The children themselves decided which work was good enough to be published in the regular school magazine, or displayed in special places in the classroom. In this way, a shared sense of aesthetic values was established.

In time, the children were able to recognise that what was good work for one child might be less so for another, but that certain criteria such as sincerity, effort and originality remained the same. A school culture and learning community developed in which sincerity and respect were paramount. The children learned to trust their own assessments and to follow their own self-imposed standards, while actively contributing to the growth of shared values. Through these methods Richardson developed an approach that facilitated the growth of internal standards that were continually rising, as opposed to the externally imposed fixed standards common in schooling today.

The question of Richardson’s legacy is complex. Some would argue that short-lived experimental schools such as Oruaiti are little more than aberrations on our educational horizon. Frequently led by captivating individuals, they blaze across the sky and then fade from view. English art critic and poet Sir Herbert Read was of this opinion when he visited New Zealand in 1954 and was shown examples of the art and language work done by pupils at Oruaiti School. After looking over the drawings and photographs, Read is said to have replied, “Well, as I travel the world, I find these odd people in little schools doing these extraordinary things, but it goes no further, you know.”

Read’s critique remains at the centre of the debate today between those who advocate the league table, test-and-teach approach to education, which is increasingly the norm, and those who promote a broader, more progressive educational view. The Oruaiti experiment offers an example of the way in which progressive educational ideas played out in a New Zealand classroom setting. What shape did these ideas take? What was left out? What was added to? What remains? In this sense an examination of Richardson’s progressive educational methods can be viewed as a timely counterpoint to the standardised teach-and-test approach, raising questions that remain important to policy makers, teachers, parents and children alike.

Although there are some very good general histories of the state education system in New Zealand, records of individual experimental schools remain scarce. Books written by New Zealand schoolteachers about their own pedagogy and teaching are rare, and educational biographies of exceptional New Zealand teachers even more so. One researcher has suggested that there is a need for educational historians

to be much more sensitive to tentative notions of alternative possibilities, to schemes that went awry, to short lived schools with distinctive approaches, in order to escape the teleology of traditional New Zealand educational history.

Examining the Oruaiti School experiment presents one such possibility.

What’s more, to explore this legacy is to present a dimension of educational culture that was not being reproduced in other settings at this time. The Oruaiti experiment not only had a profound influence on the children and their families, but also shaped the practice of visiting art specialists, who carried these progressive ideals into New Zealand schools under the auspices of the Art and Craft Branch of the Department of Education.

In a speech titled “The Historian and Heritage Issues”, New Zealand historian Michael King could have been talking about educational history when he warned: “There is a danger in living in communities that are forever shedding old skins and making new ones”, for in doing this, he said:

We erase the reference points by which people recognise their community and feel that their present is connected to a past. If people don’t feel that they have a past, that they only live in some kind of sensation-dominated continuous present, then it is more difficult for them to believe that they have a future.

This historical framing is reflected in the organisation of this book, which interweaves chapters on Richardson’s early life and experience at Oruaiti with the development of art and craft in the primary school from 1900 to 1960.

Over the course of my research I visited Richardson several times, staying with him and his partner, Helen, at their home in Henderson Valley, Auckland. We began a long correspondence about his experience as a teacher and learner, during which we exchanged over 300 letters and which continued until a year before he died. Much of the material in this book is drawn from the letters he wrote between 2005 and 2010.

Richardson’s rural upbringing on Waiheke Island and the arrival of an early mentor were to have a profound influence on his ideas about teaching and learning. These formative influences are the focus of Chapter 2, which describes his early education on the farm and his first experiences of formal schooling.

Chapter 3 outlines the development of manual and technical education—the precursors or art and craft education—and examines the different theories about child development that shaped ideas about teaching and learning in the 1900s to 1920s.

In the 1920s and 1930s the progressive education movement had a great influence on ideas about the role of art education. Chapter 4 discusses initiatives such as the La Trobe Scheme, and the Carnegie grants, which provided a conduit for the new ideas about teaching and learning that were reflected in the 1929 Syllabus of Instruction.

In 1941 the war provided an opening for further reforms in art and crafts education. Chapter 5 examines the Emergency Education Scheme and the way this provided both a catalyst and a foundation for the birth of the Art and Craft branch of the Department of Education in 1946.

Richardson began teaching at Oruaiti School in 1949. Chapter 6 describes his beginnings in the small isolated community and the permissions he received from the Department of Education to experiment with new methods.

At Oruaiti, learning was organised thematically, based around children’s individual interests and the local environment. Art and science were not viewed in isolation from each other, but rather each provided a gateway to learning in another domain. Chapter 7 considers Richardson’s orientation to science and his development of an environmental curriculum. As his curriculum developed, Richardson defined the children’s expressive process as “integration”. One child’s integrated study of eels, and their thoughts about this as an adult, provides an example of this way of working.

Although Richardson and his school became a showcase for progressive education, the term itself did not sit well with him. Chapter 8 considers his child-centred approach in relation to the progressive movement and the way in which his methods led to the growth of aesthetic standards in the classroom. Richardson’s scientific background shaped his orientation to art education and to expressive work more broadly. His approach stood in contrast to that promoted by the Art and Craft branch of the Department of Education and many of the art and craft advisers, who largely adopted an expressionist interpretation of child art.

Richardson had an uneasy relationship with the bureaucracy of education. He was on the outside in terms of his methods and ideas, but on the inside in terms of the strong support he received from within the Department of Education. Chapter 9 locates his work at Oruaiti in the context of the Department’s educational reforms and considers how the specialist advisers who spent time at the school both contributed to the development of art practices and were influenced themselves in terms of their ideas about teaching, learning and creative work.

In broad terms Richardson was protected from the top in terms of the permission he received to experiment, but on a local level the intimate scale of the New Zealand educational landscape served to amplify ideological differences and exacerbate personal tensions in ways that ultimately had a negative impact on both the individuals involved and the momentum of the reforms. Chapter 10 examines these divergences in the context of the end of the Oruaiti experiment and the reorganisation of the Art and Craft Branch of the Department of Education.

After leaving Oruaiti School Richardson became principal of two much larger primary schools in New Zealand, before moving to the United States where he continued teaching, largely at universities. After 3 years abroad he resumed teaching in New Zealand, retiring in 1987. Chapter 11 examines his later years and the ways in which his work has been recognised since.

An enduring tension in the researching of this book was Richardson’s reluctance to be contextualised historically. He did not identify with progressive educational ideals and felt himself to be largely on the outside of the educational establishment. The tensions between the forces of history and individual biography that emerged over the course of my research are examined in Chapter 12.

In 2008, prompted by Richardson’s continued expressions of nostalgia for Oruaiti School and its environs in our correspondence, I took the opportunity to return with him to the school and meet with some of his former pupils. This visit is recounted in the Epilogue (see Chapter 13) which takes the form of a short annotated photographic essay, combining images from this trip to Oruaiti with excerpts from Richardson’s letters preceding and following the visit.