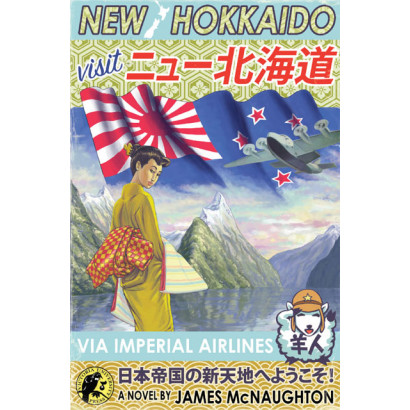

New Hokkaido

Immediate Download

Download this title immediately after purchase, and start reading straight away!

View Our Latest Ebooks

Explore our latest ebooks, catering to a wide range of reading tastes.

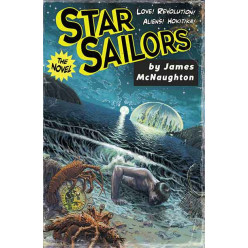

It is 1987, forty-five years after Japan conquered New Zealand, and the brutal shackles of the occupation have loosened a little: English can be spoken by natives in the home, and twenty-year-old Business English teacher Chris Ipswitch has a job at the Wellington Language Academy. But even Chris and his famous older brother—the Night Train, a retired Pan-Asian sumo champion—cannot stay out of the conflict between the Imperial Japanese Army and the Free New Zealand movement. When Chris takes it upon himself to investigate a terrible crime, he is drawn into the heart of the struggle for freedom, guided along the way by the mysterious Hitomi Kurosawa and the ghost of Kiwi rock ’n’ roll legend and martyr Johnny Lennon.

New Hokkaido is a fascinating counter-factual history and an adventure that thrills and disquiets at every turn. About the author James McNaughton grew up in Wellington and attended Victoria University, where he received an MA in Creative Writing. Two collections of poetry followed. He has lived in Australia, Israel, Japan, South Korea, the Maldives, India, and one other country, working mainly in education. He lives in Wellington with his wife and young son. This is his first novel.

From: New Hokkaido, by James McNaughton

Chapter 1: The English Academy

Ten Japanese adults, seated in two rows of five in the little classroom, are bent over their books writing their hobbies and the hobbies they guess their partner in the other row has. Chris Ipswitch stands before the blackboard, six foot three, broad-shouldered, the tallest in the room and at twenty the youngest. He wears a black suit and a white shirt, and has buzz-cut black hair and a cheerful expression on his handsome white face. He wants the class to end on a high note, to send his students out on a cloud so he can drift out too, out of the staffroom early and into the evening, into the secret New Zealand Culture Meeting at a house in Mount Victoria. He’s worked nights and weekends for three months straight now and it’s a Friday night and he wants to have a drink and meet some women. The thought of the Culture Meeting, his first, stokes his cheerful expression.

But it all depends on the deputy principal letting him go early. The excuse he has prepared is that he would like to play evening touch rugby just this once because the team’s short. It’s a request he hopes will elicit some sympathy now that he has to work weekends and is unable to play on Saturdays. Although Chris had known rugby was important to him when he gave it up for work, he didn’t realise just how important. He has lost much more than just the eighty minutes on Saturday.

Yet he’s grateful for his job. He’s the only Kiwi employed in a teaching role at the Academy, and his pay reflects that honour. His friends, by comparison, have casual labouring jobs with low pay, long hours and no security. Chris hears a lot about it. Those who have proved reliable on the last job are first on the list. But if a man misses a day, be it through sickness or a workplace injury or whatever reason, he’s bumped off the list and the first man waiting gets the job. Getting onto the list can take months of turning up at worksites pre-dawn with dozens of other hungry men and hoping someone screws up.

He has learned the names and faces of this new class. He has learned their hair as they keep their heads diligently down and compose full, natural-sounding sentences. Three students have dark black hair, one glossy black, three normal black, two a hint of very dark brown; one is flecked with grey. Another of the glossy black heads has a streak of blue dye in it. Their hair is spiky, wavy, straight, lank, luxurious, prim; all different, no repeat categories. His eye returns to the blue streak. It’s unusual for Japanese to dye their hair. He knows she’s a Settler because he has sneaked a look at the file: a civilian sent to the furthest colony of the Empire rather than prison in Japan. Two of the men are also Settlers. What their crimes were he doesn’t know. He’s looked for missing fingertips, the mark of dishonour meted out by the Yakuza, but he hasn’t had a clear view yet. There may be prosthetics involved. In any case, he has twelve weeks of this course to get a good look at their fingertips. The three of them sit separately and he wonders if they know one another.

The woman with blue hair looks up. Chris will make eye contact if she raises her hand. She doesn’t. After a long time she looks down.

‘Okay, who’s first?’ he says. ‘Is there a volunteer? Anyone?’

Some rueful looks. They’re enjoying it.

‘Okay,’ he says to the girl with the blue hair, ‘at the back, Miss Kurosawa. Please tell us your hobbies and then guess your partner’s hobbies.’

She looks at him as she tells the class: ‘I like to watch TV and sleep.’

‘Oh,’ says the class. ‘Yes.’

Miss Kurosawa turns to a woman in the row beside her, a general’s middle-aged wife. ‘I guess … am guessing?’ She looks at Chris again.

‘Either,’ he says, with a happy smile. ‘“I guess”, or, “I’m guessing that you” … ’

‘I’m guessing that you like to play basketball and listen to music.’

The class titters at the thought of the venerable general’s wife playing basketball. He knows she meant him, and it’s a pretty good guess. He is a lock, a jumping line-out specialist, or was. Music he loves, especially the banned work of Johnny Lennon. Her accurate guess, the guess of a criminal, makes him uncomfortable. The general’s wife says her hobbies. Laughter comes with each disclosure and guess. The exercise is going as he had hoped. Please, let me go early, he thinks, and imagines the deputy principal waving him away. Yet part of him hopes there will be no wave, just an annoyed grunt of refusal, because the meeting is very dangerous. And yet the danger is exciting. He laughs automatically, following the class’s cue, delighted, thinking of hot sake and girls and New Zealand music in a secret basement.

He stands by the door maintaining a respectful bow as the class file out. Even bowing, he’s taller than they are. Maybe that’s why I can do this, he thinks. Some nod slightly in return. Miss Kurosawa is last, fiddling with her bag. The room is empty when she stands in front of him, tall, taller than most Japanese men, and skinny. Her eyes have a sleepy, sardonic quality. She’s older than him, maybe twenty-five. Her lips are full and expressive. She pouts and then speaks.

‘Can you give me a private lesson?’

‘No. I’m sorry, Miss Kurosawa. That’s illegal.’ He is not even remotely interested. He would lose his job and to make matters worse she’s a Settler. She’s just trouble.

‘Oh. What a shame.’ She speaks English well, but he doesn’t ask where she learned it.

‘Thank you for your enquiry,’ he says.

She turns her lips down in a sad clown’s expression and is gone, leaving a wake of musky perfume. Trouble.

He packs up quickly, excited, sure for some reason that the deputy principal will let him go early. As he closes the classroom door his older colleague, Masuda, simultaneously closes his.

‘Sorry, sir,’ Chris says, as he must to Masuda for occupying the same space unexpectedly. Masuda glares at him. Deep furrows line his forehead. His spectacles flash. He is always angry with Chris because he, Masuda, is an English teacher who can’t really speak English, and although he’s forty-five and Chris is only twenty, Chris is a much better teacher. The fact that Chris is a native speaker doesn’t diminish the insult to Masuda’s pride, and Chris must always use the most respectful Japanese speech when addressing him and suffer sharp rebukes for the slightest slip. Masuda’s spectacles flash again. He’s building up a full head of steam. Probably, Chris thinks, because my class could be heard laughing and left the room happier than his. He stands rigidly, waiting for his senior to leave first. But of course Masuda doesn’t leave; he marches toward Chris, who reminds himself that the man’s bark is worse than his bite.

‘Teach your subject. Don’t play games.’

Chris bows. ‘Yes, sir.’

Masuda turns and Chris remains bowing until the strike of his heels has echoed away.

Chris enters the staffroom with his eyes down, making himself a shadow. His desk, cluttered like the others with piles of books and documents on the verge of toppling, is at the back of the room beside the rear entrance. Unusually, the teachers have gathered at the front, before the platform on which the principal and deputy principal sit. The senior Business English teacher stands in the centre of the group, holding court. Excited, he strikes his palm with his fist repeatedly.

‘Yes,’ he cries, ‘it sets a precedent. If the uprising in Paris is not put down, France will fall. Already there are stirrings in Berlin. Even the Germans are talking about freedom. The Soviet Union must fix its internal problems or it will cease to exist and we will be left alone to hold China. Will the US stand and watch us in the Pacific then? No!’

The teacher’s cry of anger sends a shiver up Chris’s spine. He tidies his desk quietly, invisibly. There is silence. They’ve seen me, he thinks. He closes a drawer and stands, as if deep in thought but hurrying, oblivious to everything but his own desk. Picking up his briefcase, he turns to notice the silent knot of teachers. Expressing surprise, he bows and apologises.

The teachers reluctantly disband and return to their desks.

He remains bowing until all are seated, then he approaches the altar-like structure at the front of the room. ‘Sorry,’ he says as he bows to the deputy principal.

A grunt. The frog-like hand waves as soon as he begins his request. Chris is dismissed.

They can talk now, he thinks as he walks quickly away down the corridor, fighting an urge to punch the air and run out into the street. The news he has heard is even more thrilling because it will be gold at the New Zealand Culture Meeting and sure to impress the women there. And I have a job, he thinks. Not many my age have money. If I meet someone I’ll be able to take her out.

He steps into the early darkness of June and pauses at the top of the school steps, between the armed sentries on either side of the door. A gust of wind buffets him and whips the large Japanese flag high above the huge concrete Central Administration Centre that dominates uptown. But higher than the red circle on white, great clouds are tumbling across the dark blue sky in the west, rolling and roiling as they go, as if freed and stampeding all the way from Paris.