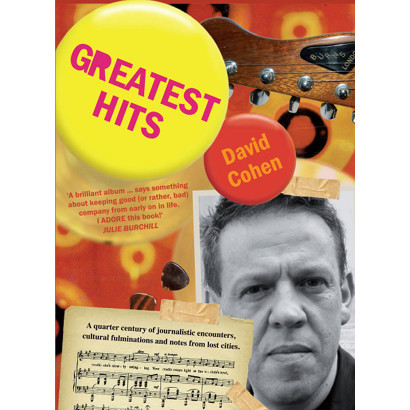

Greatest Hits

Immediate Download

Download this title immediately after purchase, and start reading straight away!

View Our Latest Ebooks

Explore our latest ebooks, catering to a wide range of reading tastes.

A quarter century of journalistic encounters, cultural fulminations and notes from lost cities.

A high-school dropout from the Hutt Valley who accidentally discovered journalism, David Cohen offers an unorthodox and often provocative take on the world he encounters. His collected writing dispatched from points north and south has been published in journals as various as the Guardian, New York Times, NZ Listener and Jerusalem Report, and includes a media column in NBR and a sheaf of book and music reviews.

"A brilliant album … says something about keeping good (or rather, bad) company from early on in life. I ADORE this book!" – Julie Burchill

"The singular Mr Cohen, with this fancy prose style and arch wit, dares to make reading a pleasure. This book will raise your IQ." – Steve Braunias

From: Greatest Hits, by David Cohen

Bono

PAUL HEWSON, BETTER KNOWN TO millions of rock followers as plain Bono, is said to be a generous guy. The man with the NASCAR glasses is so accommodating that on the eve of the band’s last album release, How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, he gave a few concert tickets away to fans in exchange for an honest opinion on which mix of the album’s terrific opener, “Vertigo”, might sound best as an iPod commercial. These days, Hewson also spends a good deal of time on the phone offering advice on world affairs to British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Yet, for a passing moment in the band’s 25-year history, he was less than considerate towards me.

An odd claim, but to the best of my knowledge correct: I am the only journalist in New Zealand to have had his own printed words performed by the U2 frontman. What’s more, it happened in front of 40,000 fans at Wellington’s Athletic Park, on 8 November 1989. That was when Hewson—pardon the deviation from standard arts writer style, but formally identifying a 45-year-old family man by a childhood nickname doesn’t seem quite right—took an unscheduled break from the song set to solicit a collective opinion from the crowd on a less than ecstatic appraisal, written by one of their countrymen and published in that day’s afternoon newspaper, of his post-punk supergroup. Going by the response, they were about as impressed as he had been.

Warming to his task, Hewson riffed on a couple of lines from the offending critique—most notably an aside about the white-bread band’s late-bloomer obsession with American black music. (As critics Eric Waggoner and Bob Mehr note in their own classic put-down, Hewson’s injunction to “Play the blues, Edge!”, as captured on the documentary Rattle and Hum, does indeed stand out as “one of rock history’s most unintentionally hilarious moments”.) This, too, aroused yowls of disapproval at the Wellington show, and over subsequent days, a number of abusive letters and phone calls, evoked by what I supposed at the time to be a mildly critical rewind through the Irish band’s foozle-headed politics and frequently unremarkable music, along with a bit of a personal trip down memory lane—to do with what until that point had been my only U2 concert-going experience here.

To be fair, the venue where I had earlier seen the group belt out their hits—Wellington’s old Winter Show Buildings—had always been a dubious setting. The acoustics tended to be problematic, the line of vision to the stage a visual tease. But on the night of the show to promote their fourth LP, Unforgettable Fire (“such an album of contrasts”, as the band’s Englishman guitarist, Dave Evans, later put it to me in an interview), rock’s soon-to-be-greatest stars seemed the dodgiest item of all.

Walking onstage, enveloped in a cloud of dry ice, the band members certainly gave no indication of hard times ahead; neither did their 5,000 expectant fans, murmurously hushed as the venue’s Zeppelin spotlights momentarily dimmed to make room for the announcer’s stentorian boom, “Ladies and gentlemen … U2!”

Achtung, baby! The stage bloomed in pink incandescence as Hewson marched out of the wings—black-garbed and looking for all the world like a dead ringer for actor Robin Williams. Then came stern-faced, virtuoso guitarist Evans. Next followed no-nonsense rhythm section: drummer Larry Mullen, Jr—wearing a black T-shirt and someone else’s shoulders—joined by the bespectacled Adam Clayton, peering out from underneath a curly rug of hair.

And the rest, as they say, was hysteria—of a certain kind. For nearly two hours, the crowd appeared to surrender itself to the band’s every emotional command. They howled their appreciation for Hewson’s political pitter-patter; they trembled to every last totalitarian guitar solo—shunning chords, for the most part, in favour of big, colourful figures that tended to sound suspiciously like reworked renditions of whatever had been the previous solo—by Evans; they stood obediently for “Sunday Bloody Sunday”, “New Year’s Day” and sundry other hits from the group’s socially conscious back-catalogue.

About halfway through the set, during a hothouse rendition of “Two Hearts Beat as One”, Hewson plucked a plainly over-refreshed girl out of the throng, yanking her, not a little unsteadily, up on stage. Draping her arm across his shoulder, the singer proceeded to attempt a fast shuffle while Clayton played the song’s signature burping bass line, over and over and over again; alas, the girl appeared frozen in the headlights, and even Hewson nearly tripped on his own black heels. A couple of stagehands quickly rushed out to drag his unwitting, and by this point virtually comatose, partner to safety.

Okay, perhaps it was just another anthemic rock gig, and, to be fair, at least a few of the songs weren’t half bad. Yet, beneath the genuine theatrics of the evening there seemed to lurk a weird spirit. It was as if both the band and their fans were doing nothing more (or less) than going through the expected motions of … well, what exactly? A musical performance? A revivalist rally? A high-octane rendition of The Landmark Forum? Whatever it was, the alchemy felt purely reflexive, signalling neither genuine recognition nor real passion.

How long, as someone else once asked, how long must they sing this song?

In the piece of mine that caused the hot fuss, I also pointed out that in every art form, whether music, literature, the cinema or even lovemaking, there tends to be one golden rule of structure: tension-climax-resolve. From promising beginnings, the work of U2 appeared to have settled into a very dour groove involving lots of rattle on the first two fronts but too much ho-hum when it came to satisfying resolutions. The songs weren’t much fun, in other words.

So dire. So straight. Not only did many of these compositions lack a fun spirit, they also seemed almost wilfully sexless. Can it be any coincidence that a dozen albums on from their 1980 debut, Boy, U2 has recorded just one solitary track (“A Man and a Woman” from Atomic Bomb) devoted to carnal knowledge?

This, then, was the gist of the offending article. So great was the response to dwelling on it that even today, many years and a couple of partial career changes later, I’m still asked whether I will dare show my face at one of the band’s scheduled Auckland concerts. The question is put as if I have some lifelong problem with a group of liberal Christian millionaires from Ireland whose most obvious “problem” is having managed to address, chastely, nearly all of the serious issues currently facing the world—apartheid, famine, American foreign policy, Thatcherism, Iran-Contra, inner-city blues, etc.

This is far from being the case. Taken on its own merits, I enjoy most forms of gospel music, including its Christian rock cousin. (Come to think of it, one of the band’s nicest songs is a straight reading of the Old Testament’s Psalm 40, the album closer from War.) Nor do I have a problem with heartfelt expressions of chastity, providing I’m not involved.

Social causes? It’s been said before—by me, I think—that while many artistic types, be they poets, critics, movie-makers, playwrights or, especially, rock performers, may be proficient enough depicters of personal feeling and individual reality—think Lou Reed’s fractured ode to smack, “Street Hassle”; think Alejandro Escovedo riding a musical boxcar across the Mexican-US border on his spooky A Man Under the Influence—they do, on the whole, tend to make bad authorities on public or social-policy matters. It’s the Dave Dobbyn syndrome: being politically serious not for any particular purpose but simply because looking politically serious will hopefully make you look very artistically important.

Left or right, it really makes no difference. In the case of an act like U2, the problem is exacerbated by the fact that they have been led to believe that events like their happy-clappy concerts actually carry enduring weight. In fact, they do not. They offer bad ideas. Repetitive guitar solos. A slightly scary ambience. The only other exceptional hallmark is their baffling sense of moral outrage over a corporate world that has, truth be told, treated U2 rather nicely, thank you.

If only Paul Hewson could do as much for his occasional antipodean critic.