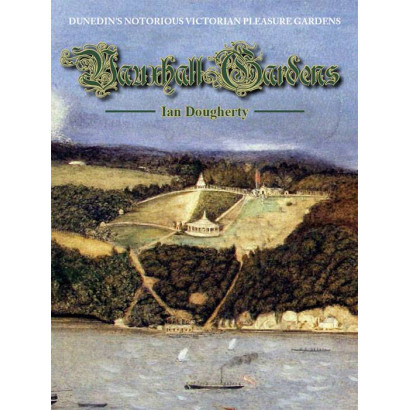

Vauxhall Gardens: Dunedin's Notorious Victorian Pleasure Gardens

Immediate Download

Download this title immediately after purchase, and start reading straight away!

View Our Latest Ebooks

Explore our latest ebooks, catering to a wide range of reading tastes.

Vauxhall Gardens was Dunedin's pride and shame. Built on wealth from the 1860s Otago goldrush, Henry Farley's pleasure gardens attracted gold miners and townsfolk in their thousands. But its reputation for quality entertainment was tarnished by allegations of prostitution and debauchery.

From: Vauxhall Gardens, by Ian Dougherty

Chapter 1

Henry Farley’s Miniature Paradise

One story told of the genesis of Vauxhall Gardens has a certain charm.

‘And one day, as all the new sounds of the stirring waterfront echoed about the crude wooden houses scattered here and there, a man stood on Bell Hill thinking of the gold diggers, the rapidly-rising population and the lack of entertainment then existing. His eyes came to rest on the picturesque headland across the harbour, he saw the native bush clothing the slopes of the hill and hanging over the water and, turning, he saw the gold escort come trundling down Princes street below him. This man’s name was Henry Farley, later the builder of the Royal Arcade. It was he who had visualised the population crossing the harbour to a miniature paradise where the worries of life could be temporarily forgotten amid enjoyment, the like of which had hitherto never been known in New Zealand.’1

Henry Charles Farley was born in the village of Severn Stoke in the English county of Worcestershire on 5 October 1823, a son of Giles and Anne Farley. Henry decided not to follow his father into farming and instead worked as a licensed tea dealer in the Welsh market town of Presteign(e). On 30 June 1851 the 27-year-old married Mary Jones, a teenage daughter of a local shopkeeper, John Jones, and his wife Ann Jones. Henry and Mary had two sons: Charles and Herbert.

Henry Farley was lured half way round the world by the prospect of gold, not from the ground but from miners’ pockets. Six feet tall and lean with blue eyes and a hooked nose, he ventured first to Australia, where he set himself up as a property speculator in the mining town of Ballarat in the heart of the Victorian goldfields. In addition to buying and selling land, Farley purchased a couple of hotels: the Gin Palace Hotel and the John O’Groat Hotel, which, with its associated concert hall, was one of the best known establishments in the town. Mary Farley didn’t take to colonial life and returned to Britain with the boys. When news reached Ballarat of another big gold discovery, this time in the New Zealand province of Otago in May 1861, Farley joined the rush of miners and entrepreneurs to sail across the Tasman Sea to the new antipodean El Dorado.2

Farley and the other ‘New Chums’ (one of the politer of the descriptions of the newcomers) and the wealth they revealed transformed the province and its fledgling capital and principal port of Dunedin, which had been founded in 1848 by the breakaway Free Church of Scotland after a fight within the Scottish Presbyterian Church. According to one description of the town immediately before the discovery of gold:

‘After twelve years of settlement, Dunedin was still a straggling village of no beauty and less pretensions with a population of about two thousand. The so-called roads which served as thoroughfares for pedestrian, horse and bullock traffic alike, were unlighted and devoid of metal, with the consequence that, in times of rain, they became a treacherous morass of miry clay which merited for the settlement the name of Mud-Edin.’3

More than 20,000 people descended on Otago through Dunedin in the latter half of 1861. In one day in October, 1500 people disembarked at the town’s tiny jetty. Most of the migrants were multi-national gold diggers wearing uniformed flannel shirts and moleskin trousers and wielding picks and shovels, tin dishes and crude wooden cradles. Sluice guns, stamper batteries and dredges followed. Some of the miners came from other settlements in New Zealand but by far the greater number, like Henry Farley, flocked in from Australia and particularly the dwindling Victorian goldfields. Most headed straight to the golden hinterland but sufficient remained in or returned to Dunedin to help boost the town’s population to 5850 by the end of the year, with another 673 people aboard ships in the harbour.4 As one historian has commented, ‘Almost overnight the staid and leisurely little provincial capital became a bustling, rowdy, raffish outpost of the goldfields.’5

Within three years the population of Dunedin reached 15,121 and the town was on its way to becoming the most populous and prosperous centre, busiest port and commercial and industrial capital of New Zealand. Major capital works were carried out. The hill on which Farley was said to be standing when he conceived his pleasure gardens would soon be levelled for harbour reclamation and the site of the Free Church of Scotland’s inspiring First Church.

The free-spending gold diggers demanded supplies and equipment and craved entertainment. Theatres, cafes, billiard saloons, singing and dancing saloons sprang up to entertain the transient population. The number of hotels in Dunedin surged from five in 1860 to peak at 87 in 1864.6

Keen for a slice of the action, Farley put his Australian capital to work and set himself up as a land agent and property developer in Dunedin. Within a few months of arriving in the town he had established the first of his major enterprises, Farley’s Arcade (later known as Fleet Street, then Farley’s Royal Arcade, then Broadway), a walkway lined with 54 shops linking High and Maclaggan streets, and auctioned off the leases. The weekly Otago Witness described the Arcade as ‘a depot for the reception of every description of merchandise, edibles, drinkables, wearables, and (if the word be good English) smokables’ for the town’s burgeoning population. The lessees included the Arcade Hotel, shoemakers, cabinetmakers, chemists, crockery stores, tailors, fruiterers, hairdressers, iron-mongers, news agents, booksellers, butchers, drapers, grocers, land agents, a music shop, an oyster salon, restaurants, coffee shops, seed merchants, stationers, tobacconists, wine, spirits and beer merchants, fishmongers and tentmakers.7

A short stroll to the north, in Princes Street on the western side of the Cutting just north of Dowling Street, he constructed another major enterprise, Farley’s Buildings, comprising rented shops, offices and the Dunedin Music Hall, later known as Farley’s Hall. The tenants included the Dunedin Savings Bank, solicitors, a surgeon, a dentist, a chemist, photographers, stationers, dressmakers, a tobacconist, grocers, fruiterers and the City Buffet hotel, coffee room and restaurant. Farley operated his land agency from one of the offices. He hired out the music hall for parties, balls, lectures and public meetings. Farley’s Buildings have since been much modified and put to a variety of commercial purposes.8

Farley’s other town-centre property developments included the purchase of Tickle’s Dunedin Commercial Salerooms in Princes Street, just south of the Stafford Street corner, where he replaced the wooden salerooms with a three-storyed brick structure – one of the most substantial buildings in Dunedin at the time. Farley also speculated in land elsewhere in the town, including the suburb of Kaikorai, where Farley Street carries his name.9 His land deals were so extensive that he was soon being blamed for pushing up land prices by speculating in town lots and re-letting land at a large profit.10 The entrepreneur established his most ambitious enterprise across the bay.

Part of the picturesque headland Farley spied across the harbour belonged to William Cutten, who had arrived in Dunedin on the first settler ship, the John Wickliffe, in 1848 and married the eldest daughter of one of the ‘founding fathers’, William Cargill. Cutten was variously an auctioneer, immigration officer, commissioner of crown lands, co-founder of the Otago Daily Times, editor of the Otago Witness and a provincial and national politician. He had found the bush-clothed ‘suburban’ land difficult to access and made little use of it. He lived further round the harbour towards the town in a grand house called Belmont on Goat Hill (Sunshine) in the suburb of Musselburgh.11

On 1 October 1862 Farley entered into a lease with Cutten for 20 acres of the headland for a period of 21 years at an annual rental of £300.12 Here he established the Vauxhall Pleasure and Tea Gardens, the first such pleasure gardens in New Zealand, which he named after Vauxhall Gardens in London and modelled it on this and similar gardens in London and the Cremorne Gardens in Melbourne (see London’s Vauxhall Gardens).13

London’s Vauxhall Gardens

Vauxhall Gardens was the most famous and long-lived of the pleasure gardens established throughout London in the 17th and 18th centuries to provide places for public entertainment. The New Spring Garden at Vauxhall, as it was originally known, opened to the public in 1661, 201 years before its Dunedin namesake. At first it was little more than a few shrub-lined walks but new walks were added and tree-lined avenues planted, abounding with statues and famous effects such as a cascading waterfall. In its heyday it sported arcades, supper alcoves decorated by contemporary artists, a theatre for ballet productions and a concert hall where an orchestra and organ played and small-scale operas were presented. There were also equestrian and circus performances, fireworks displays, hot air and gas filled balloon rides and demonstrations of parachuting from balloons, which cost one man his life when the chute failed.

The gardens had its seedier side. After sundown, the so-called ‘Dark Walk’ (the other garden walks were illuminated by thousands of coloured lamps) was said to be frequented by ‘strumpets’ or ‘ladies of ill-repute’ and their clients. There were stories of women accidentally strolling down this walk, being mistaken for ‘ladies of questionable virtue’ and accosted.

After entertaining patrons for nearly two centuries, declining popularity forced Vauxhall Gardens to close in 1859, three years before Farley opened his antipodean version. Everything that could be moved was auctioned, the land was sub-divided, and streets and houses obliterated all traces of the gardens.14

Farley promised that ‘no expense will be spared to render these Gardens the resort of pleasure-seekers, and others in search of recreation.’ An initial part of the expense involved dealing with a couple of logistical problems he and the workmen he employed for the task faced in establishing the gardens across the harbour from the town – the same problems that had beset Cutten. First, land access via Andersons Bay was too far and too difficult to walk comfortably. Men could ride a horse to the gardens and families were able to take a carriage as far as the stables Farley built at the foot of the headland, but most people in the town owned neither horse nor carriage and the road was rough. Second, the site was on top of a natural fortress above a steep cliff.

Farley solved the first problem by having a small jetty built at the bottom of the cliff so visitors could cross the water directly from the town jetty. He overcame the second problem by having a tramway cut up the cliff face. Two counterbalanced cars connected by a cable ran up and down parallel railway tracks. One car ascended while the other descended, worked by simple machinery operated from a tramway house. The tramway was not completed until just before the gardens opened and most of the building material for the gardens was shipped across the harbour, landed at the jetty and hauled up a steep, gravel path cut at an angle across the face of the cliff. The path was also available to visitors as an alternative to the tramway.15 Another path zigzagged up from the back of the headland, from what became Larnach Road, for people arriving via Andersons Bay. A ticket box guarded each entrance path.16 The ambitious tramway soon fell into disuse after which all visitors had to climb the hill.

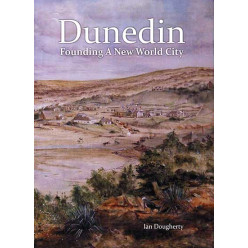

Dunedin in 1862, showing Henry Farley’s elongated Arcade (right) running back from Maclaggan Street through to High Street. Farley had the narrow pathway between the rows of wooden shops widened and a row of two-storey brick shops built on the far side of the Arcade in 1866. He had the near side rebuilt to match, and the carriageway asphalted and roofed, in 1875. Farley established his famous gardens across the harbour on the bush-clad headland (far left).

Hocken Collections, University of Otago

Farley’s men cleared the dense bush from part of the gently sloping hilltop site and drained and laid out the grounds. In the center of the clearing they built a wooden rotunda for dancing. The large, round building was about 50 yards in circumference, had a roofed-in pointed top and open railed sides and, in the middle, an elevated semi-enclosed area for a band. A small bar and ladies dining room was later attached and ladies dressing rooms built close by.

Behind the rotunda and slightly to the right stood a single storey wooden ‘bar refreshment saloon’ that initially consisted of a long, wide hall-like room 45 feet by 25 feet, with a high stud about 18 feet between floor and ceiling. Carvings adorned the front and interior of the high gable hotel. During the day natural light shone through large windows made partly of coloured glass. Behind a long counter appeared what an Otago Daily Times reporter described as ‘a goodly array of choice liquids, presided over and dealt out by a fair goddess, who put the finishing stroke to the prettiness with which the bar was arranged.’ To this single room saloon was later added a ladies refreshment room about 18 feet by 15 feet, a private sitting room 12 feet by 12 feet, two bedrooms with attached bathrooms ‘set apart for gushing newly married couples to spend their honeymoon in’, and a large cellar under the bar.

To the right of the hotel Farley set aside a large and reasonably level area of cleared ground around which a post and rail fence was run up forming an oval about 150 yards in circumference. This area became the outdoor ‘gymnasium’ for various sports and games. Swings were erected and plans made for a variety of other amusements, including a rifle range, archery ground, quoit ground, lawn bowling green and two skittle alleys in which players attempted to knock over wooden pins with a ball. Around the fenced clearing 12 ‘handsomely designed’ bowers or summer houses were later built for visitors seeking refreshments or rest.17

Statues were erected throughout the grounds and ‘labyrinthine walks’ cut through the thick bush on either side of the hotel along which seats were conveniently placed. The Otago Daily Times gushed:

‘The result is a practical edition of, a “New Zealand Bush Made Easy;” for while sauntering along these paths – here matted with rich grass or clover, there inlaid with twisted and laced roots – the visitor may see on either hand, good illustrations of how “bush lawyers” creep and cling, how supple-jacks hang pendulous and woven into screens, how charmingly fresh ferns and sombre pines form natural arches and bowers, and of what a wealth of beauty there is, even in a single fern or cabbage tree, when fairly examined amidst its native woodlands wild.’18

Indeed, the newspaper assured its readers, ‘the lovers of trees and ferns, may enjoy the sight of as beautiful a collection as they could wish to see. Some of the Fern trees are exceedingly pretty, they would be worth a great deal in a botanical garden.’ The stunning views back across the harbour to the town and hills were an additional natural attraction.19

Ever the entrepreneur, Farley also leased some land from one of the few local residents, Adam Begg, in the gully at the back of the gardens and employed a man named Hodgkinson to make bricks for sale in the town.20

Farley regarded Vauxhall Gardens as another property development, like the Arcade and Farley’s Buildings, that he would establish and then lease to others. He gave prospective lessees plenty of scope, offering to let by tender together or separately for three, six or 12 months the hotel, tea gardens, confectionery department, archery ground, quoit ground, bowling green and rifle range. When tenders closed on 15 December 1862 there were apparently no acceptable offers.21

Farley appointed as the first manager of the gardens Thomas Hetherington, who also held the beer and wine licence granted by the provincial government in early December. It came with a warning. The provincial superintendent, John Richardson, who heard the application along with the provincial secretary and solicitor, told Hetherington:

‘But before any great expense was incurred, the applicant should understand, that remote as the gardens would be from the police, the Government would keep a very vigilant eye to see that no irregularities were allowed. If such should be the case during the present year, in all probability the licence would not be renewed.’22

Hetherington had applied for a liquor licence that would allow the Vauxhall Gardens hotel to sell wine and beer until 11 p.m. but was granted a licence that only ran until 10 p.m. He was immediately in trouble with the law. In the Resident Magistrate’s Court on December 30 he pleaded guilty to keeping the hotel open after 10 o’clock. The police told the court that the hotel was open beyond the legal closing time on its first two days of operation, on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, and the police did not interfere, but when the breach continued and it was kept open until 10.45 p.m. on Boxing Day, ‘they could not allow it to pass unnoticed’. Hetherington offered as excuses that he did not know the time, and that there was ‘over-pressure of business.’ The resident magistrate, Alfred Strode, suggested he buy a clock, warned him not to do it again and ordered him to pay the cost of the summons. Hetherington was back in court six weeks later, this time for having the hotel open all night. He was fined 40 shillings and costs.23 An application to extend the licensing hours until midnight was declined.24

Farley’s men worked ‘vigorously’ and had made enough progress to enable him to open Vauxhall Gardens just before Christmas and the start of the busy summer holiday season, less than three months after taking over the lease of the land. The people of Dunedin, who for several weeks had watched his workers transform the bush-clad hilltop across the bay, were given a chance to inspect the gardens on Monday 22 December. They had to make their own transport arrangements, taking the long way round on foot, horseback or carriage, or across the bay in one of the small, oared, wooden boats operated by professional boatmen who plied the harbour.25

The following day a new steamer was hastily brought into service to transport 30 ‘gentlemen’ Farley had invited to ‘a cold collation’ and private inspection of the grounds and facilities. With no suitable vessel available and the opening day looming, a desperate Farley had coveted a small iron steamer that had recently been shipped across from Melbourne in components and was being re-assembled by Dunedin shipwright Archibald Keith for use on Lake Wakatipu. Those plans were shelved and Keith rushed to finish the vessel in time for the gardens opening. The vessel was launched further down the harbour at Port Chalmers on 20 December and plied between the town jetty and the gardens jetty for the first time three days later carrying Farley’s guests.26

After a delay while someone hastily returned to the town for the forgotten forks, lunch was consumed in the hotel, a variety of toasts proposed and drunk with enthusiasm and the party returned to the steamer, which Otago Daily Times co-founder and editor Julius Vogel christened Nugget and smashed a bottle of champagne over the bows. The steamer could comfortably carry 40 passengers and complete the trip in eight minutes.

The gardens’ formal opening fete scheduled for the Tuesday evening was postponed until the following evening, Christmas Eve, when a large number of people paid the one shilling admission price to enter the gardens. Hundreds of Chinese lanterns lit up the rotunda and threw soft colours over the grounds. Before dark the wide-eyed visitors watched the first hot air balloon in Otago make its ascent from the clearing behind the rotunda, pass across the bay and over the town.27 Unlike the exploits at Vauxhall Gardens’ London namesake, this and later balloon ascents were unmanned.

Farley wanted to attract the widest cross-section of townsfolk to the gardens. For the first full day of operation, Christmas Day, a public holiday, he promised Christmas sports and prizes that would ‘astonish both Old and New Identity’ (broad descriptions applied to those who had arrived before the goldrush, mainly from Scotland, and those who had arrived since, mainly from Victoria). The sporting activities at Vauxhall, and elsewhere, were for men only. Women were ‘ladies’ and they were spectators but Farley urged them to come early to enjoy the fresh air, a dance and a good cup of tea with cream in it.28 It was a good selling point; many of the public places of entertainment in Dunedin such as pubs and theatres were regarded as unsuitable for ‘ladies’. Farley benefited from Christmas Day and Easter not being regarded by the Free Church of Scotland as days of quiet reverence although he faced a weekly damper from the church’s views on strict observance of the Sabbath as a day for prayer not play.

Christmas Day at Vauxhall Gardens was partly overshadowed by teething troubles with the steamer service. The Nugget was advertised to leave the town jetty for the gardens jetty every half an hour from nine a.m. until midnight for a return fare of one shilling. Robert McCannell of Pelichet Bay to the north of the town, grumbled in a letter to the editor of the Otago Daily Times that he visited the gardens on Christmas Day and was surprised at the treatment of visitors on the jetty. He wrote that the Nugget left the gardens jetty at 11.45 p.m. crowded with passengers, promising to return but never did, yet there was a full complement of passengers waiting with return tickets, including ‘a few respectable ladies forced to stand in the cold’. Passengers left behind had been forced to pay an extra fare and return via other vessels and it was after two a.m. when he finally landed at the town jetty. McCannell suggested that it would be in Farley’s interests to make transport arrangements with the professional boatmen who plied the harbour, rather than with the steamer, adding that if Farley expected to be supported by the public, he must humour the public.29

Worse still, Keith found it difficult to keep to a regular half-hour timetable, even after the steamer went onto a daily schedule that didn’t begin until two p.m. Within days of opening, Farley was publicly apologising for any shortcomings during the Christmas holidays as a result of the uncertain departure of the hastily prepared vessel, which he promised would be decorated and repainted and every effort made to start punctually.30

Farley continued to rely on a steamer service but individual boatmen also took paying passengers between the town and gardens jetties. They too were early on under fire. The short-lived Dunedin newspaper, the Evening News, reported:

’We consider it our duty to acquaint the public that an imposition, similar in its nature to the extortions of the London cabmen, is being practised daily by the Dunedin boatmen, and we think the sooner these worthies are brought to their senses the better. The fare to Vauxhall and back by the steamer Nugget, is one shilling; the usual charge by a whale boat one shilling each way. You can please yourself, of course, which conveyance to take, but don’t take the ipse dixit of the boatmen, who tells you the steamer has just gone, and won’t start again for an hour; and, on your return from the Gardens, don’t believe these aquatic satellites if they swear that the steamer has broken down, and taking advantage of your credulity, extort double or quadruple fares.’31

Boxing Day, a day of ‘semi-business and semi-pleasure’, saw another large attendance at the gardens and the Otago Daily Times predicted that Farley’s ‘speculation promises to be a great success, for the number of visitors so far has, we should imagine, exceeded even the most sanguine expectations.’32 The Boxing Day attendance was achieved despite a rival event in the town. Shadrach Jones, an English doctor turned entrepreneur, staged admission-free Boxing Day ‘Old English Games’ in the yard of the Commercial Hotel in High Street, just as he had the previous year in the yard of the Provincial Hotel in Stafford Street. (The 100 yards had to be run in two 50-yard sprints there and back.)33

Farley and Jones had much in common and that would later include Vauxhall Gardens. Married with eight children, Jones worked as a doctor in England for several years before emigrating in 1851 to the Victorian goldfields town of Bendigo (then known as Sandhurst), where he is said to have amassed a large fortune as a commission agent and auctioneer with business partner Charles Bird. The pair followed the goldrush to Otago in October 1861, bought the Provincial and Commercial hotels and converted parts of them into theatres. (The Royal Princess Theatre at the Provincial was initially created by screening off the animal stalls on either side of the saleyards at the back of the pub each evening and folding down a stage at one end.) Jones brought to Dunedin theatrical companies, dancers, boxers and billiards champions. Notable performers included the English Opera Company, the United States actor Joseph Jefferson (regarded by many as the greatest actor of his day) and one of Jones’ mates from Bendigo, Charles Thatcher, who made his living out of a talent for writing and performing topical verses set to popular tunes.34

Farley had initially created the fenced area of cleared ground to the right of the hotel in the hope that the recently formed Caledonian Society of Otago would choose Vauxhall Gardens for its inaugural annual gathering on the first two days of the New Year. The distinctly Scottish society opted instead to hold the highland sports days at the Grange Estate of John Harris – a lawyer, politician, businessman, Caledonian Society president and another Cargill son-in-law – at Pelichet Bay, where the games spilled over into a third day. After failing to secure the patronage of the Caledonian Society, the Englishman Farley instead went ahead with a ‘grand revival of old English games’ on New Year’s Day, in direct competition with the first day of the Caledonian Society’s gathering. In the evening, two more hot air balloons were sent up from the gardens.35

The enterprising medicine man Shadrach Edward Robert Jones. He was described by Robert Fulton in his history of early medical practice in Otago and Southland as ‘a short, stout, rubicund individual, with a “draught board” waistcoat, fat cigar in his mouth, sturdy bulldog at heel, and a lavish display of jewellery’.

Alexander Turnbull Library

Finding suitable workers for the gardens was a problem, particularly over the holiday period. On New Year’s Day Farley advertised for a timekeeper ‘with good character’ for the Nugget. Two days later he advertised for three ‘highly respectable young ladies’ and three waiters to assist in the hotel for a few hours in the evening, to start immediately.36

Good dance band musicians were also in short supply although apparently so were good dancers. Shortly after the opening day, the Evening News told its readers:

‘We are aware that the proprietor has used every exertion to get a good orchestra, and it is a great pity that a better band is not obtainable to enliven the proceedings. The dancers (particularly the ladies) want a good deal of practice before they can do justice to “Varsoviana”, “Scottische”, or “Polka”; and it is pretty evident most of those who have patronised the rotunda are direct importations from countries where jigs and reels are more popular than the compositions of Jullien and D’Albert.’37

Farley had other concerns too. The sports ground to the right of the hotel had been cleared in a hurry and a large quantity of valuable timber dumped into the gully at the back of the gardens. About five p.m. on 4 January 1863 a fire started near the crest of the ridge at the rear of the hotel and was driven by a strong wind down the gully and into the timber. Fearing for the hotel building Farley had a break cut through the bush in a line with the hotel and the turf removed to form a trench. Heavy overnight rain extinguished the fire but a large area of bush was destroyed.38

The old English games held at Vauxhall Gardens on New Year’s Day in 1863 were a combination of athletic sports and fairground amusements. The silver cup was manufactured by Mr Hyman, a Princes Street watchmaker and jeweller.

Otago Daily Times 31 December 1862

Farley found that families and single men, many of whom were miners, were an uneasy mix and in early 1863 he converted two acres of land into a private picnic garden ‘where pleasure-seekers can enjoy all the conventional appliances of al fresco dinners, without being intruded on by the general company in the gardens.’ The fenced off area with its seats and bowers was to be ‘essentially for the amusement of the more respectable classes, and more particularly ladies and children.’ Private picnic parties could make their own eating arrangements or have them taken care of by the Dunedin firm of Waters Morton and Co, which boasted that it could cater for up to 500 people in a few hours notice.39

Public holidays continued to be the busiest days at the gardens. On Monday 23 March 1863 the gardens played host to its first Otago Anniversary Day celebrations, marking the arrival on 23 March 1848 of the John Wickliffe carrying the Otago province’s first organised settlers. A quadrille band provided dance music throughout the day and one large ‘semi-private’ picnic party took advantage of the private picnic garden. Vauxhall Gardens also provided a spectacular view of the first Anniversary Day regatta on the harbour immediately below the gardens – something Farley had no hand in organising but capitalised on in his Anniversary Day advertisements.

In the evening the gardens staged the first of its spectacular fireworks displays courtesy of the ‘celebrated pyrotechnist’ and ‘well known artiste in that line’, ‘Professor’ Prescott. He had honed his craft at the Cremorne Gardens in Melbourne, which were established on the banks of the Yarra River in 1853 by James Ellis, who had opened similar gardens of the same name in London. The Melbourne gardens were later acquired by theatrical entrepreneur George Coppin, who went bankrupt in 1863 and the gardens were closed, putting Prescott out of work.

Prescott created the Vauxhall Gardens pyrotechnics in a ‘firework manufactory’ erected on the grounds. Farley charged a premium admission price of two shillings and sixpence for this grand gala night, which drew a large crowd. The fireworks were, according to the Otago Witness, ‘very varied in design, and altogether so excellent as to afford the highest satisfaction to those present.’ The success was aided by the wind lulling during the display.40

Prescott’s ability to light up the skies and patrons’ eyes was a ticket-box winner. If townsfolk needed any further prompting, the sight and sound of the fireworks coming from the other side of the harbour was a gigantic advertising sign in the sky. The grand gala nights featuring Prescott’s ‘stunning pyrotechnic displays’ became a regular Monday night feature at the gardens. Farley also introduced regular Friday night balls for which he also charged the premium admission price. Every day the quadrille band was engaged to play from three p.m. until 10 p.m.41

Farley’s frustrations continued in trying to provide a reliable ferry service. The Nugget only lasted a few weeks on the harbour before being cut in two, transported to Kingston at the south end of Lake Wakatipu, riveted back together and re-launched to become the first steamer on the lake, the vessel’s original destination. Farley briefly called on the services of another steamer, the Lady of the Lake, to take passengers to and from the gardens. (The paddle steamer had been built in Scotland in sections, re-assembled at Pelichet Bay and launched a few months earlier.) He then imported from Melbourne his own small steamer, Minerva, which carried about 60 passengers and ran each day from two in the afternoon until seven at night, or midnight on Monday gala and Friday ball nights. Farley initially decided to operate the service for free and continue to charge visitors to the gardens a general admission price of one shilling, and two shillings and sixpence on gala and ball nights. The Minerva illustrated a further frustration for Farley in trying to operate a ferry service on a shallow harbour. At low tide, the passengers had to transfer from the Minerva to a smaller boat to make the town jetty.42

On Easter Monday on 6 April 1863, another public holiday, Farley added to the regular Monday fare of quadrille band and Prescott pyrotechnics by providing another of Hyman’s silver cups for the winner of a foot race. This time he charged a race entry fee of five shillings.43 A week later Prescott pulled out all the stops for the gala night, letting off ‘more than usually elaborate devices and unusually powerful rockets’ to the delight of a large gathering.44

The British royal family was an asset to the colonial entertainment business. The anniversary of Queen Victoria’s birthday on 24 May was celebrated as a public holiday throughout the colony. In 1863 it fell on a Sunday and the following day was declared a public holiday. At Vauxhall Gardens, Farley hosted an afternoon of holiday sports, and a fireworks display and fancy dress ball in the evening. The Otago Daily Times noted that ‘a large concourse of pleasure-seekers’ visited the gardens and that ‘Mr Farley has undoubtedly succeeded in making Vauxhall a favourite haunt, and his spirited catering for public amusement deserves the hearty support of the public.’45

When a sailing ship finally reached Dunedin the following month with ‘news’ of the marriage of Victoria’s oldest son and heir to her crown, Edward, the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), to a Danish princess, Alexandra, in London on 10 March 1863, the town marked the occasion in grand style. The provincial government declared 30 June an official day of celebration and voted £500 for the festivities. Dunedin’s shops and offices shut, the streets were decorated with ‘triumphal arches’, the muddy parts of George Street were covered with road metal for a procession to the Botanical Gardens to plant memorial oaks, an ox was roasted in the Octagon and a banquet was held at Jones’ Provincial Hotel. Farley cashed in on the celebrations by holding a grand fancy dress masquerade ball at Vauxhall Gardens. As a special attraction, ladies were asked to come early and have a slice of royal bride cake, which contained four golden wedding rings. Farley acquired the services of a brass band for those wanting to dance in the rotunda, and the evening climaxed with another of Prescott’s ‘magnificent displays of fireworks’.46

While the Prince of Wales’ wedding was a one-off celebration, the anniversary of his birthday, 9 November, was an annual public holiday, with public offices and all but a few shops closed for the day. Farley again tried to make the most of the opportunity to fill time and empty pockets but the weather was against him. It started raining just after lunch and continued with slight intervals all afternoon and evening, causing the cancellation of the gymnastic games planned for the afternoon. In the evening, Farley went ahead with a fancy dress ball at which music was provided by Mr Walker’s Brass Band.47

It was a damp ending to what had been a successful first year for New Zealand’s first pleasure gardens. Henry Farley had established the gardens quickly, provided popular entertainment never before seen in Dunedin, done his best to overcome transport problems and satisfy the diverse range of patrons and tried to establish a good reputation for the gardens. The latter was about to come under damning attack.

Notes

Chapter 1

Henry Farley’s Miniature Paradise

1 D.C. Mooney writing in the Otago Daily Times, Dunedin, 23 Mar 1938, p 17. A rehashed version of the story was later printed in the Evening Star, Dunedin, 19 Jan 1963, p 10.

2 Border Post and Stannum Miner, Stanthorpe, 18 Jun 1880. Donald Gordon, ‘The Ubiquitous Henry Farley’, Otago Settlers News, Otago Settlers Museum, Dunedin, Dec 2005, p 4 (The article was later reproduced in the Otago Daily Times, 2 Jan 2008, p 30). Marriage Register, Henry Charles Farley and Mary Jones, Presteign(e), 30 Jun 1851, no 153, General Register Office, England. Marriage Register, Henry Farley and Elizabeth Ann Wheeler, Ballarat, 2 Oct 1867, no 4431, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Melbourne. Otago Witness, Dunedin, 17 Jul 1880, p 17. Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 17 Jun 1880, p 5. The weights, measures and currency of the time have been retained in the text. To convert inches to centimetres multiply by 2.54, feet to metres multiply by 0.3048 and yards to metres multiply by 0.9144. To convert acres to hectares multiply by 0.4046865. To convert pounds to kilograms multiply by 0.4535924. There are 12 pence in a shilling and 20 shillings in a pound. A guinea is 21 shillings. A sovereign is a gold coin nominally worth one pound.

3 Alexander McLintock, The History of Otago: The Origins and Growth of a Wakefield Class Settlement, Otago Centennial Historical Publications, Dunedin, 1949, p 423.

4 David Richmond, ‘Dunedin in the 1860’s: Some Aspects of Settlement’, Master of Arts, Geography, University of Otago, Dunedin, 1972, pp 28-31.

5 Kenneth McDonald, City of Dunedin: A Century of Civic Enterprise, Dunedin City Corporation, Dunedin, 1965, p 50.

6 Mary McCarthy, ‘A City in Transition: Diversification in the Social Life of Dunedin 1860-1864’, Bachelor of Arts (Honours), History, University of Otago, Dunedin, 1977, pp 29-31. Ray Hargreaves, Barmaids, Billiards, Nobblers & Rat-pits: Pub Life in Goldrush Dunedin, Otago Heritage Books, Dunedin, 1992, p 6.

7 Otago Witness, 8 Mar 1862, p 4; 9 Aug 1862, p 8.

8 Daily Telegraph, Dunedin, 12 Dec 1863, p 2.

9 Otago Daily Times, 15 Oct 1955, p 3.

10 [D.D. Wheeler], The New Zealand Goldfields 1861: A Series of Letters Reprinted from the Melbourne Argus, Hocken Library, Dunedin, 1976, pp 11, 20-1.

11 Stuart Greif and Hardwicke Knight, Cutten: Letters Revealing the Life and Times of William Henry Cutten, The Forgotten Pioneer, Dunedin, 1979, p 13.

12 Otago Daily Times, 25 Feb 1864, p 3.

13 Otago Daily Times, 10 Dec 1862, p 1.

14 David Cole and Alan Borg, Vauxhall Gardens: A History, Yale University Press, London, 2011. James Southworth, Vauxhall Gardens: A Chapter in the Social History of England, Columbia University Press, New York, 1941. W.S. Scott, Green Retreats: The Story of Vauxhall Gardens 1661-1859, Odhams Press, London, 1955. Warwick Wroth, The London Pleasure Gardens of the Eighteenth Century, Macmillan & Co, London, 1896, pp 286-326.

15 Otago Daily Times, 19 Nov 1862, p 5; 24 Dec 1862, p 5; 31 Dec 1862, p 3.

16 Henry Duckworth, Early Otago: History of Anderson’s Bay from 1844 to December 1921 and Tomahawk from 1857 to March 1923, Coulls Somerville Wilkie, Dunedin, 1923, p 35.

17 Daily Telegraph, 13 Feb 1863, p 2; 2 Mar 1863, p 2. Otago Daily Times, 19 Nov 1862, p 5; 3 Dec 1862, p 6; 24 Dec 1862, p 5; 25 Feb 1864, p 3; 23 Mar 1938, p 17. [Robert Whitworth], Grimshaw, Bagshaw & Bradshaw’s Comic Guide to Dunedin, Geddes Brothers, Dunedin, 1869, p 17.

18 Otago Daily Times, 31 Dec 1862, p 4.

19 Otago Daily Times, 24 Dec 1862, p 5.

20 Duckworth, Early Otago, p 35.

21 Otago Daily Times, 9 Dec 1862, p 3.

22 Otago Daily Times, 3 Dec 1862, p 6.

23 Otago Daily Times, 31 Dec 1862, p 5; 13 Feb 1863, p 5. See also Robert Fulton, Medical Practice in Otago and Southland in the Early Days, Otago Daily Times & Witness Newspaper Company, Dunedin, 1922, p 201.

24 Otago Daily Times, 7 Jan 1863, p 5.

25 Otago Daily Times, 22 Dec 1862, p 5.

26 Frederick McCluskey, Down the Bay: The History of the Ferries on Otago Harbour, New Zealand Ship & Marine Society/ Wellington Maritime Museum & Gallery, Wellington, 1995, p 29. Gavin McLean, Otago Harbour: Currents of Controversy, Otago Harbour Board, Dunedin, 1985, pp 287, 308.

27 Otago Daily Times, 23 Dec 1862, p 5; 24 Dec 1862, p 5; 25 Dec 1862, p 4.

28 Otago Daily Times, 24 Dec 1862, p 3; 25 Dec 1862, p 3.

29 Otago Daily Times, 26 Dec 1862, p 4.

30 Otago Daily Times, 31 Dec 1862, p 3.

31 Evening News, Dunedin, 26 Dec 1862, p 4.

32 Otago Daily Times, 27 Dec 1862, p 5.

33 James Strachan, ‘James Strachan’s Experiences: My First Twelve Years on my Own Commencing 20 Apr 1856, Nearly 61 Years Ago’, [1917], qMS-1933, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. Otago Daily Times, 26 Dec 1862, p 7; 27 Dec 1862, p 4.

34 Dunedin Leader, Dunedin, 12 Mar 1864, pp 1, 16. Fulton, Medical Practice, p 198. George Griffiths, ‘Jones, Shadrach Edward Robert (1822-1895)’, in Bill Oliver (editor), The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography: Volume One 1769-1869, Allen & Unwin/Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 1990, p 213. Hargreaves, Barmaids, pp 12, 23-4. Otago Witness, 22 Aug 1895, p 3. Peter Downes, Shadows on the Stage: Theatre in New Zealand – the First 70 Years, John McIndoe, Dunedin, 1975, pp 44-63. Robert Hoskins, Goldfield Balladeer: The Life and Times of the Celebrated Charles R. Thatcher, Collins, Auckland, 1977. Tapanui Courier and Central Districts Gazette, Tapanui, 7 Aug 1895, p 5.

35 Otago Daily Times, 29 Dec 1862, p 5; 31 Dec 1862, pp 3, 4; 1 Jan 1863, p 5; 3 Jan 1863, p 5; 6 Jan 1863, p 5.

36 Otago Daily Times, 1 Jan 1863, p 3; 3 Jan 1863, p 3.

37 Evening News, 26 Dec 1862, p 4.

38 Otago Daily Times, 5 Jan 1863, p 5; 6 Jan 1863, p 4.

39 Otago Daily Times, 30 Dec 1862, p 5; 31 Dec 1862, p 3.

40 Daily Telegraph, 25 Mar 1863, p 2. Otago Daily Times, 23 Mar 1863, pp 5, 6; 25 Feb 1864, p 3. Otago Witness, 28 Mar 1863, p 2.

41 Otago Daily Times, 25 Mar 1863, p 3. Otago Witness, 4 Apr 1863, p 5.

42 McCluskey, Down the Bay, pp 10, 30-1, 38-42, 48. Otago Daily Times, 30 Mar 1863, p 4; 18 Apr 1863, p 1.

43 Otago Daily Times, 4 Apr 1863, p 6.

44 Otago Daily Times, 13 Apr 1863, p 4; 14 Apr 1863, p 5.

45 Otago Daily Times, 25 May 1863, p 3; 26 May 1864, p 4.

46 Otago Daily Times, 30 Jun 1863, p 3; 1 Jul 1863, pp 4-6.

47 Dunedin Leader, 14 Nov 1863, p 2. Otago Daily Times, 8 Nov 1863, p 5; 11 Nov 1863, p 5.