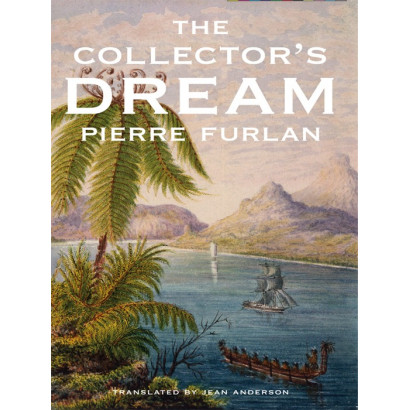

The Collector's Dream

Immediate Download

Download this title immediately after purchase, and start reading straight away!

View Our Latest Ebooks

Explore our latest ebooks, catering to a wide range of reading tastes.

A holidaying writer becomes entranced by the story of two great New Zealand eccentrics. First there is Franklin Bodmin, self-taught genius and inventor of the crinkled hairpin and the first modern carburettor, who became an entrepreneur in America, living out the dreams of success of an entire generation. Growing up in Invercargill, in the shadow of this superhero father, Will Bodmin chooses a different path, travelling to England to become an unorthodox Jungian art therapist and one of the greatest ever collectors of documents and works of art relating to the South Pacific.

Drawn into archival byways and the intricacies of family lore, our author finds himself retracing Will’s search for the elusive 19th-century pamphlet that would make his collection complete. From one man’s obsessive accumulation of objects and knowledge emerges a meditation on both the human conviction that life, in spite of its irrational moments, can be deciphered, and on a young nation’s obsession with its past.

Praise for the French edition of The Collector’s Dream:

‘This is a beautiful tale. It could also be extremely dark if Pierre Furlan didn’t share with all first-rate storytellers a talent for studding his narrative with anecdotes, stories and unexpected vistas, all in the tradition of great literary journeys.’

—Daniel Martin, La Montagne

‘True stories, legends, tall tales – the novel weaves a narrative where every object, letter or book triggers a tale, picturesque or pitiful. But the novel is not merely a collection of stories: its structure, as well as revealing Furlan’s mastery of the story-teller’s art, is also a real reflection on what inspires and gives life to literature.’

—Alain Nicolas, L’Humanité

PIERRE FURLAN is the author of six books of fiction, and is also a leading literary translator, of Paul Auster, Russell Banks, Alan Duff and Elizabeth Knox, amongst many others. He was the French writer in residence at the Randell Cottage in Wellington in 2004-2005, and Bluebeard's Workshop and Other Stories was published by VUP in 2007. Born in southwestern France, he spent his adolescence in California and studied at UC Berkeley, before settling permanently in Paris.

JEAN ANDERSON is Senior Lecturer in French at the School of Languages and Cultures at Victoria University of Wellington, and Director of the Centre for Literary Translation.

From: The Collector's Dream, by Pierre Furlan

Sails

This is a story about heroes. A story about sails on the Pacific, sails that swelled like Will Bodmin’s heart, when the restless, endless sea called him towards another world. He could sense the immensity of the ocean when he left New Zealand for Europe in 1949. Standing on deck at night, he saw it reflected in the southern skies as he stared up at them, trying to make out the constellation the Greeks called the Argo, that other ship dismantled two centuries earlier by dull-spirited astronomers who broke it down into mere parts: Keel, Sails, Stern. He could see it, he was sure.

Forty years later, on his way back, he flew over that same sea. There were no more great liners linking the South Pacific to Europe. The oceans, now crisscrossed in all directions, sliced through by the steel hulls of enormous oil tankers and other cargo ships, were just dirty puddles struggling to survive. The great adventures of the tall ships were hidden away in books, in his own books especially, in the collection he had built up over many years – the best, the most original collection since the one Rex de C. Nan Kivell had donated to Australia.

This is a story about heroes who are sometimes ridiculous. A father and his son. The encyclopedias tell us the father was a great inventor: in 1900 he designed and patented the crinkled hairpin. Previously these pins were straight and fell out of women’s chignons and hats. While this invention didn’t have quite the same impact as sliced bread, it was still an ingenious arrangement, nearly as simple as E=mc2, and it earned Franklin Bodmin a fortune. He founded a company in New York, with the writer Mark Twain as deputy director, to market his hairpin worldwide; he would go on to create a great many other devices, including a prototype carburettor fitted to American army trucks in the 1920s. And as for his son, a bookseller who knew him well in England states that Will was a gentle and eccentric man with a prodigious memory who would arrive every year at the Antiquarian Book Fair in York and plant himself in front of the great neo-classical Assembly Rooms, waiting for the doors to open so he could be one of the first inside. He would then work his way round the stalls with the most extraordinary determination and concentration, and might be found kneeling beneath a table or between two piles of books, a torch in his hand to shine on the most out-of-reach volumes, shoulders hunched forward, collar turned up, and wearing workman’s earmuffs to block out the background noise, the whole chattering, deluded world that, in Will Bodmin’s opinion, was like some nasty soup where only the scum floats to the top. He would peer and poke; he had developed a sixth sense that led him to some astonishing discoveries. But throughout the second half of his life he was obsessed by a pamphlet that had once slipped through his fingers in England: a little tract printed in 1831, denouncing the violent acts of Governor Ralph Darling in Australia.

The pamphlet told the story of two soldiers, Joseph Sudds and Patrick Thompson, who tired of keeping an eye on the convicts in the colony of New South Wales and committed a few minor misdeeds, for which they were to be transported to Tasmania. But Governor Darling, convinced the two of them had deliberately broken the law in order to get out of the army, decided they were getting off far too lightly. So he organised a parade at which the two accused, shackles on their ankles and steel-spiked collars tight around their necks, were drummed out of their regiment and condemned to wear these irons while they worked on the roads. As a result of this treatment Sudds died after just five days, and Thompson went mad. Later, cleared by the Crown of this and several other atrocities, Darling would go on to become Knight Grand Cross of Hanover.

Will Bodmin, the bookseller explained, had taken a strong, almost personal dislike to this relatively unknown governor. He felt the tract was a unique moment in the history of human rights: a step towards ending the slavery that still binds humanity – all the more so, paradoxically, since we claim to be free. And there was another reason for Bodmin’s quest: the pamphlet was one of the rarest items relating to the history of colonisation in the South Pacific. If he could have got his hands on it, he might have considered himself the greatest collector in the field. And then he would have been able to speak out, to say what was on his mind without needing to write vengeful letters to the people who ruled the planet, in particular New Zealand. They would have listened to him, he believed. The indictment of Darling would have opened Will’s heart and loosened his tongue: it would have set him free.

The last known specimen had disappeared from the Australian National Library in 1972, possibly stolen, but there were thought to be one or two others in circulation, and Will believed one of these was destined to be his, that he would track one down. ‘A quest,’ according to the bookseller in York, ‘that was a bit ridiculous, actually, when you realise the Darling contains nothing new and is of no value except to a collector. Just an empty shell, really.’ But one that glittered. The bookseller shrugged.

As far as my own involvement goes, I set out on the track of Will Bodmin, but as I found out more about him, he seemed both closer and more distant, always slipping away just as I thought I had him pinned down. I saw him as a superstitious man, fascinated by ghosts and the supernatural. He believed in the most outrageous things, simply because they were trumpeted in the English tabloids. He sent his mother newspaper clippings about an American who, in 1960, had supposedly perfected a camera that could photograph the human soul. ‘Priests will find their task much easier now,’ he wrote, ‘because they’ll be able to see how corrupt or pure our souls are.’ That same year, in Switzerland, he fell into ecstasies over an ancient invention on show at an exhibition in Valais. As early as 1788 a Swiss had apparently built a motorised vehicle and driven it through the city of Sion, patenting the main components in 1807. ‘But nobody,’ Will despaired, ‘was the least bit interested.’ On the 29th of May 1960, he sent his mother an article from the Guardian about someone finding the Abominable Snowman’s jawbone. The following month, he complained that a motorboat had inadvertently cut off one of the feet of the ‘poor’ Loch Ness monster. He also struck up a correspondence with one Mr O’Connell, frequently mentioned in the papers as having managed to photograph said monster.

Maybe it’s not so surprising that he believed in the weirdest discoveries, given that he was the son of a pretty strange inventor. Or that he deliberately looked for inventions that would be bold enough to outshine those of his father – a man he admits he didn’t love, but who controlled his entire existence.

This is a story about heroes, because once we have listed every quality in them that is exactly like our own qualities, there is still some other element left over, something grandiose, like gigantic dark shadows dancing on a white curtain, making improbable gestures as they try to save themselves, and perhaps to save us too.