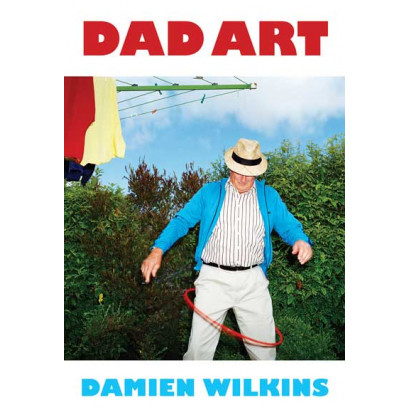

Dad Art

From: Dad Art, by Damien Wilkins

One

How strange to step off the street one minute and then twenty minutes later to be safely on fire. Puffs of smoke were coming from his pale half-naked body, rising past his nose, drifting up towards the Where’s Wally? poster on the ceiling of the clinic. Some part of him thought, okay, why not, it ends right here. Middle-aged white men were a huge problem in the world. If the chance arose to incinerate one—yes, on the whole, go for it. Except it was another one of these same men in charge.

The doctor was cauterising the ten-centimetre wound he’d opened on Michael’s chest (suspected basal cell carcinoma).

Michael was trying to calm himself through flippancy. He laughed, curiously weightless, fearless, as if a little high from the four lots of anaesthetic they’d injected into the spot above his left breast. For a moment it had seemed they couldn’t anaesthetise him. He was the Man Who Always Felt Pain. You feel that? the doctor had said. Yes, said Michael. You feel that now. Yes. Yes? Even now? Okay, another one. The doctor was getting tired of it. Michael thought: am I paying extra for these extra shots or am I eating into the clinic’s profit margin? Doctor: That you don’t feel? A little, Michael said again, pretty sure he felt prickling. Okay, said the doctor, bored, disbelieving, you don’t feel that. It was an assertion. Let’s work.

‘I smell burning,’ Michael said into their faces. The nurse, whose name he’d forgotten, was there too, handing the doctor things.

‘Little bit,’ said the doctor. He was Polish, serious and comic in the same moment. A sort of humble show-off. Michael, always a sucker for accented English, liked him. In some deep way he believed he didn’t speak English correctly either. Did anyone?

‘You all right down there, love?’ said the nurse. She hummed to the radio they’d turned on the minute he’d crawled onto the bed-like thing. He felt the tight cool cover-sheet against the skin of his bare ankles, reassuringly as if someone kind had placed her slender fingers there to hold him in place. Some people probably tried to run.

He was calling to mind as many of the Words of the Day as he could. He got an email every morning. Raumati was summer. His worst childhood sunburn was in Raumati, the town. It was autumn now: Ngahuru. And soon Takurua. He had the days of the week and the months pinned to the fridge. What did manuhiri mean? Repeating the word he briefly overcame his situation.

‘This is good music,’ said the doctor. ‘It’s Billy Joel.’

‘Is it Billy Joel?’ said the nurse.

‘Yes. Is it? I think so.’

‘I’m not sure.’

Michael couldn’t let it go. ‘It’s Elton John.’ He sought medical help rarely but always enjoyed it, the sudden vulnerability, a panicky feeling, then surrender. Do it to me, whatever you have to do. The Polish doctor, having pressed his eye-piece to the spot (BCC for sure because it’s shiny when I look), had been hesitant about the time available for the procedure and had said at first they’d have to schedule for next month. But Michael said his GP had told him this appointment was about removal. He’d had the thing for ten or eleven months—confessing six to his GP so she wouldn’t consider him a complete baby. You want to do it now? said the doctor, looking into his eyes. Yes, said Michael, with an emphasis he discovered as he spoke. Then let’s do it. With medicine, he liked the sense of capture, the no-place-else-to-be of it. Then the sense of release. Fly away little bird, have another day. He’d always been released—that helped. Not like others: his mother, he thought of. Now his father.

‘John, Joel, similar,’ said the doctor. ‘What’s your job?’

‘Acoustic engineer,’ said Michael, underneath him.

‘Music? You record?’

‘More design, acoustics of buildings.’

The nurse smiled. ‘Interesting jobs we hear about, don’t we, Lukasz?’

‘In restaurants,’ said the doctor, ‘I can’t hear what my wife says.’ He had needle and thread now, was moving in and out from Michael’s chest with a certain flourish, patting the area with his fingers, bending closer to inspect.

‘Places are too noisy,’ said the nurse.

Elton John, Michael thought suddenly, was the father of very young children. He’d done everything. Now he was Papa. He was a pop genius who’d ruled the world. But everyone wanted children. Where were these thoughts coming from? Michael’s daughter, Samantha, was arriving in town on the weekend to stay with him for a night. She was going to a wedding. Sam was 22, living in Auckland. He missed her dreadfully, always had. The minute she’d left home to attend university a part of his life ended with such crushing force he went to bed in the afternoon immediately after taking her to the airport. His headache lasted five days and even now the mildest newspaper photo of a parent with an adolescent child could tip him into hollowing sorrow. It was unbearable to think about. It was embarrassing. Vanessa was taken aback. What was all this grandstanding? She was the young woman’s mother and she was sad but excited. Oh sure, he could be excited. He understood the process. Still, in many ways he believed his significant life work was over and all of this was afterthought and waiting around. If I die before I see her again, thought Michael—but what was he thinking? If I die—well, medicine meant that too. His father had regularly had things chopped out.

Lukasz the Pole continued to stitch and peer. Hold me closer tiny dancer.

When a friend recently had his testicles pierced by needles, his wife had been holding his hand in the surgery. He’d asked her to. Aerated was the wrong word. Drained? No. Aspirated. Poor bloke. He, Michael, had no one. Certainly not Vanessa, who would never know about these moments of him being on fire, just as he would never again know about whatever she might go through on this sort of scale of minor crisis, minor mortal shake-up. Minor was what he hoped. In twenty-plus years of marriage dot dot dot—he didn’t have an original thought about what was astonishingly amputated when that relationship (impoverished word) ended—the defining one of his life, let’s face it—and this seemed right. He wasn’t original. These feelings weren’t. He and Vanessa lasted a year after Sam left home. But ‘lasted’ was wrong, as if it was ‘suffered’—no, the year hadn’t been bad or much different from other recent years. Yet everything was loosened. He was probably morose a fair bit of the time. He didn’t understand it. Mentally they were prepared for the change and had talked about coping strategies. There were plenty of ‘empty nest syndrome’ columns to read. They went to Rarotonga for a week in winter. Fundamentally, as a unit of caring, they felt under- if not fully unemployed. Meanwhile, their daughter was thriving.

Vanessa had left Wellington and was renting in Auckland, working at a veterinary clinic on the North Shore, swimming in the sea in the evenings—a thing she’d never shown any interest in before. He’d been temporarily aghast at her quick thinking: she now lived in the same city as Samantha! It would seem grasping and weird if he were to follow.

He remembered a thing she’d said one friendly night when they were sorting out house stuff: But we had all that good sex. It was so true.

Perhaps the nurse would have held his hand if he’d asked. She was in her mid fifties, he guessed—his age—though she’d lived a harder life. Nurses did. Her wavy hair was style-less, her face ruddy and freckly, led by a purposeful chin—boldly a kind of immoveable ‘before’ image in this place of cosmetic makeovers. They were in a converted Mount Victoria villa whose main business, it appeared, was cosmetic skin procedures for women. Botox, nuking varicose veins. His own GP had shares in it. Waiting for his appointment, Michael had been the only male. Middle-aged women, often creeping gingerly and wearing sunglasses, were farewelled by their first names at the front desk. Will you drive yourself, Patricia? Oh, I have a taxi waiting. Farewell, my darling.

Lukasz was round-faced with a frizz of blondish hair. He wore a white coat that ended above the knee and gold-framed glasses—give him a pipe and he would have been at home as a psychoanalyst in the 1950s.

Where the fuck was Wally?

The doctor paused and tapped Michael’s arm. ‘What do you think for a new flag for New Zealand? Acoustic engineer. Hmm. Maybe a big ear.’

‘Ha,’ said Michael.

‘I like the old flag,’ said the nurse.

‘No,’ said Lukasz, ‘because the ear symbolises, hey, Let’s listen to each other. Hear what’s going on in this country.’

‘Fair call,’ said Michael.

‘Forty thousand children admitted each year to hospital for preventable diseases. Forty thousand! Most of these because of poor housing.’ He tapped Michael again. ‘For a health professional in this country, you got to think, Maybe I’ll re-train as a builder or a plumber to fit central heating, you know? Serious.’

‘Maybe on our national flag,’ said Michael, ‘put a shivering child in front of a heater that’s not plugged in.’

The doctor looked at him over his mask, weighing this up. ‘What colour background?’

‘Stop it,’ said the nurse.

The song on the radio had changed but—magically—it was indeed Billy Joel now, whom he’d always loathed. But why? He was trying to give up anathema, to say nothing is anathema to me though without implying that meant soft and anything goes. Anything did not go, including this bankrupt shitty mean blind lying bullying National government. He knew a guy, a lawyer, who’d had one of those semi-legendary public service careers ending as a Deputy Chief Executive in various ministries and he’d told Michael at a party, ‘We’ve never been ruled by a greater bunch of philistines in our entire history.’ But Michael could cut others some slack. Meanwhile Joel, it turned out, was actually fine. He’d read the long New Yorker profile. Joel was likeable, even a little more than that. He’d done something surprising which Michael couldn’t remember now. He should really cancel his subscription given how much remained unread. In the end, it was the cartoons that kept it all afloat. He always turned to the back first, to the caption contest, which as a New Zealander he couldn’t enter. He followed Bill Manhire on Twitter who had pointed that out and since then he always thought about it and wondered if New Zealand’s greatest living poet had composed a whole bunch of unsent entries. Here, trying to find some funny line, he came slap up against his severe literalism—an aspect Vanessa had noted first as adorable, much later as problematic. Engineers were spectrumy.

The nurse was back and asking again how he was. She called him love again. He liked it.

Billy Joel had two new hips and in rehearsal sang bawdy lyrics to ‘Just the Way You Are’.

The doctor was squeezing at the sutured wound with both hands. ‘Good,’ he said. ‘Maybe a couple more though.’ Michael watched the needle rise and fall, aware only of being moved around by the force of the sewing, the untender pressing of the doctor’s European hands.

‘Do you know Scots College?’ said Lukasz. ‘My son goes there. They have an auditorium with the most beautiful sound.’

Michael nodded. ‘Peter Jackson gave them the money, I think.’

‘We all gave them the money. We are always giving them money. But yes, Peter Jackson too. Big pockets. Big shorts with big pockets. Have you been to this auditorium?’

‘No,’ said Michael.

‘Hmm,’ said the doctor, unimpressed maybe or simply absorbed once more in his work.

Just as fast Michael wanted it to be over now. This feeling was familiar too, entering the phase when novelty has long departed and a creeping terror, surprisingly strong for such low stakes, registers as dizziness, slight nausea. He had to fight the urge to throw off the Pole, grab his shirt and flee the room.

Lukasz was finally finishing up. He said he was happy with what he’d done and told the nurse to bandage it. She approached Michael, humming. ‘Skin is so tough, isn’t it,’ she said. ‘Amazing.’

To distract himself, he thought of the immediate future. This evening he had his te reo class. It was only two hours away. Would he feel up to it? With self-pity he considered not attending, as a marker of what he’d gone through under the knife. He always felt uncertain about delivering his pēpehā. Some days he had it by heart, other days only its constituent parts surfaced, chunks of language he couldn’t jigsaw back into place. Just think of who you are, their tutor, Kelly, would say. Forget the formula for a mo. Forget this pressure on the Māori. The reo ain’t going nowhere, it’ll be there for you. Just think: Who am I? If that was the question, his answers would come. His river and his mountain. Interestingly and appealingly he didn’t have to struggle to locate himself along these lines. Lots of the others in the class did. What could my mountain be? they begged Kelly. Could a harbour be a river, could a stream? Tangi te keo was where he’d lived his entire married life and lots of other time too in student flats. They’d walked the dog in the town belt for her lifespan. The dog remained unnamed or had a name only she knew, in accordance with an Ursula Le Guin story Vanessa had read in which Eve unnames all the animals, returning them to their dignity and mystery. But, Michael had argued, I didn’t consent to my name either. But, said Ness, you can do something about that. Vanessa’s trip as a vet from training through employment was a slow evolution of a moral sense which, she’d been saying for a few years, would lead her to leave the profession she loved. There were too many practices and circumstances she consented to which had no basis in what she—and most vets—believed about animals’ lives. Presently, however, she had to make a living. She read Peter Singer and J.M. Coetzee and corrected ‘pet’ to ‘companion animal’. She couldn’t throw out her shoes though or her lovely Italian boots.

Post-op, Michael thought again, the te reo class might be a step too far. Wouldn’t he need to rest, be careful, have a drink, watch TV? He’d been loaned a box set of Game of Thrones Season Four. He’d not seen any of the previous seasons. Then in two days he was meeting someone called Melissa at the Lido Café. He’d been on the dating site for six months and had met and un-met five women. He considered, with a kind of relief, that given his bandaged wound and fairly substantial surgery, he wouldn’t need to be thinking about sleeping with Melissa straight off, not that he knew anything about the likelihood or desirability of this. Their emails had been rightly cautious. Their exchanged photos highly curated. She appeared in hers at the end of a long row of grapevines in a sunhat. Suggesting what? Affluence? Alcohol? Perhaps she’d simply been to the Martinborough Food and Wine Festival. He was also outdoors, by Lake Wanaka, the mountains behind him. The photo was five years old and suggested what? Money again? Ruggedness and adventure? Taste? Choosing Wanaka over nasty Queenstown. His daughter had taken the photo on their last family holiday. Mt Aspiring was somewhere in the background. ‘It’s an aspirational photo, Dad,’ Sam told him. The sunglasses made him look younger, didn’t they? Though how fast did sunglasses date? Faster than he thought no doubt. He looked like some old ski instructor, or the bloke who drove the snow-making machine. Anyway, he’d bring up his wound fairly early so Melissa wouldn’t have to be thinking about it either or at least she’d know he was probably not thinking about getting physical straight-off, or that that was the reason for the date. Hot women near you want sex. This could be a tension-easer in his limited experience. What was he talking about? He’d slept with one of the five women and that had been led by her. He’d happily gone along for the ride. The trick was going to be raising the subject of the surgery without putting her off him for good. Please stay interested, if you would, in my disgusting failing patched-up body and let’s see where this takes us because when I’m mended, sex between us could be pretty wonderful, just not now—that was the general idea. Or how about just keep quiet. Slowly she’d get the idea she wouldn’t need her pepper spray. Back on track, Game of Thrones, he’d heard, had plenty of nudity.

‘With this,’ the nurse said, ‘you can have showers because it’s waterproof but no swimming for about six weeks. And I’ll give you a spare bandage. When this one gets too scuzzy, you can change it.’

Thing is, Melissa, I won’t be swimming for six weeks. He wasn’t a swimmer but the fact that the nurse considered it a possibility was a boost. He took a quiet pride in his shoulders if not the dimpling skin around his ribs, his circumspect paunch. And there was a pool at the new place which he’d been in a couple of times. ‘I can change it myself?’ he asked.

The doctor was back. ‘Do it yourself.’ He had some paperwork. When Michael was upright and putting his shirt on, the doctor asked him to sign two forms, one of which was the bill. Then he wrote out a script for pain relief. ‘Don’t wait till it’s sore, get this now. When you feel some small pain, take them.’

On the desk, Michael saw the specimen jar with its scraping of something pink and wet. Repulsive that it was him, that he’d given them this task, the administrative job of dealing with his shiny carcinoma. By all rights he should take it with him. Please leave with your own rubbish. Yet even as he stood there he was aware—of course—that worse was doing the rounds, that courier drivers were buzzing all over town with people’s … stuff. ‘They do some tests?’ he said.

‘We send it to the lab. We ring you but not for a couple of days.’ He pointed at Michael’s chest. ‘I do a good job, neat, but this area, you have to go deep and so the scar is there.’ He’d explained about the scar before he’d started. Also that his left nipple would be pulled slightly to one side because of the way the skin worked. ‘Thank you and goodbye.’ The doctor stood up and left the room while Michael was putting on his shoes.

‘Lukasz is the best,’ said the nurse with obvious pride and devotion. ‘You all right there, love?’ She touched his arm.

‘I am,’ said Michael. Then, for whatever reason, he burst into tears. He sobbed and gulped like a baby. Tears were on his shoes. He covered his face with his hands. ‘Jesus,’ he said, smiling up at the nurse, recovering.

‘It’s shock,’ she said. She held his arm as he stood. ‘And not finding Wally.’

She left the room. With his handkerchief he wiped his eyes and his nose.

On the floor beside him was his shoulder bag, bulging in a way he couldn’t figure. It looked unattractively heavy, bulbous as if it too had popped a carcinoma. He didn’t fancy lugging it now. He touched its side and felt the shape of the hardback. Yes, he’d picked up Piketty’s Capital from the sale bin at Unity. Putting on his shirt he felt the dampness under his arms—he’d been holding himself tightly as they worked on him.

He paid at reception. The only time his credit card had been handled more ceremoniously was in Japanese restaurants. It cost him $550. There was a free check-up with the nurse next week.

Outside it was sunny, strange, the air alive in his nostrils, clarity in the outlines of cars and houses, as if his eyesight had just gone up a notch. Maybe the result of the tears? The bandage on his chest tweaked him as he moved. He mihi’d himself home, holding his bag at his side so as not to strain the wound.

Te Awakairangi te awa. Really? The Hutt River? Yes, he was plugged into it as much as anywhere. Not through fishing or swimming, though he’d done both these things on occasion. He meant more the banks of the river, and the stopbanks. He meant more the constant crossing and re-crossing of the bridges. He guessed he also meant fooling around there, smoking or hiding or just hanging out. Drinking in car parks and bushes. He meant falling asleep there. The connection, when he thought about it, wasn’t entirely respectable. But it was surprisingly fierce once he’d latched on to it. And it was all a long time ago of course but still you couldn’t have history without years going by. Rivers run through it, rivers of blood, rivers of mud. Deep holes and baked stones. Droughty trickles and corded torrents. He’d seen cars carried off. No other place felt as full of him or for him. If he passed it on the motorway, driving towards the Wairarapa, without much of a thought, still one thought always came: there it is. Of course his connections were pathetic alongside other histories with a thousand years in them. But if you were asking, well, he had this answer.

He had to drive up to Waikanae and see his father tomorrow at the home, he remembered. Unless he put that off till Samantha arrived. They could both go if she had the time. Derek had been deprived of his mobility scooter not that long ago so she wouldn’t be able to take that for a spin. With its nifty panniers in which he stored the bottles of supermarket wine, he’d been known to other residents, admiringly, as the Booze Baron, distributing alcohol with a secrecy more invented than actual. The good old days.

From Te Awakairangi he and his father had taken the stones for their backyard wall—twenty yards long and almost six feet high. His dad had driven their old Landrover onto the exposed riverbed in summer—1972 or 73 or 74—and they’d loaded up. They must have done dozens of trips, careful not to wreck the back axle. Why didn’t anyone else in Lower Hutt take stones to make stuff? It wouldn’t have surprised him if it had been illegal even back then. Derek, a geologist, didn’t quite believe in the law. They cruised Lower Hutt at night looking for skips and throwing considerable amounts of crap into them. It occurred to Michael as the wall went up that they were making something if not permanent at least bloody hard to get rid of. Look at all the ancient stone walls around the world. He assumed the wall would still be there now.

In the te reo class, Michael had resisted the urge to tell the stone wall story. Was plundering your awa okay? He’d wait at least until he knew everyone a bit better. Maybe stones were a resource to be used? Did Māori pre-settlement build with stones? Pā were fortified with wood, right? Stone tools, sure. Ornaments and weapons. The sinker on a fishing line. Cooking was all stones, heating the hāngi. But larger structures? Nah he was so ignorant. I’m here because I haven’t got a clue, someone had said at the first class meeting. Kia ora, bro.