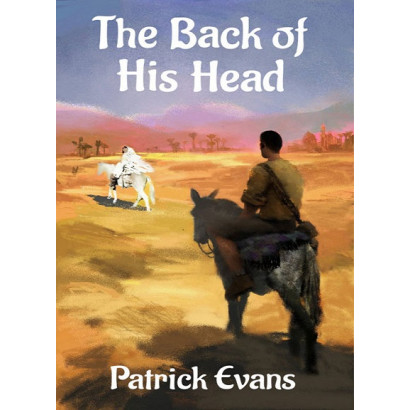

The Back of His Head

Raymond Thomas Lawrence was one of the great literary colossi to bestride the twentieth century. He turned his upbringing in conservative Canterbury and participation in the Algerian War of Independence into a series of novels that dazzled the world, and eventually won him the Nobel Prize for Literature. Seven years after Lawrence’s death, however, the four trustees of the literary trust set up to memorialise New Zealand’s greatest writer are facing rising costs and dwindling visitor numbers at the Residence.

While fending off a self-appointed biographer, they find themselves confronting the secrets of their own intimate relationships with The Master. ‘But is bumping off biographers really the sort of thing literary trusts do?’ Marjorie creaks. ‘Don’t we just handle copyright?’ The Back of His Head is a hilarious and troubling satire on the making and manipulation of literary fame, by the author of the acclaimed novel Gifted.

From: The Back of His Head, by Patrick Evans

Chapter One

One of the Master’s ashtrays is missing.

I’ve texted the other Trust members and told them to be early for tonight’s meeting: they should be here at the Residence any minute now.

I can’t tell you how angry I am. All thought of other problems falls away. It’s not that the ashtray was worth anything in itself—it’s just a paua shell Raymond picked up from the beach and stubbed his cigars in for twenty years and more, each day he wrote.

No, it’s the principle involved. We go to the trouble of keeping his house exactly as it was when he was alive and writing in it, we open it for the public good, and what’s our reward? Constant pilfering—constant pilfering. This week alone, a teaspoon, four books and a toilet roll—can you believe that? Someone would actually steal a toilet roll? Given the circumstances, it’s hardly likely to have been used by the great man himself, is it?—but apparently that doesn’t matter, that doesn’t stop them: off it goes to the black market that seems to have developed for his memorabilia, along with much of the other bric-a-brac that helps us represent the life and work of Raymond Thomas Lawrence, our greatest living author: now, of course, lamentably and officially, deceased.

We’ll start our search for today’s culprit with the most recent names from the Visitor Book, of course, as we always do when a theft occurs. For small parties such as today’s, one of the Trust members is usually enough to take them through and keep an eye on things, though when we get a large tour bus we all turn up to the Residence, and when a planeload of over-excited Danes booked in a couple of years ago we had to bring some of our gardening ladies inside to help restrain the visitors’ Viking hands. Not that there was any sign of actual pilfering, as it happened, but their scrub-faced enthusiasm was almost as bad as they milled about, bumping into furniture, and one of them actually lay full-length on Raymond’s bed, if you please, on the very spot where, the Visitors’ Brochure assures us, the Master breathed his last.

Let me take you through the Raymond Lawrence Residence now, as I begin to close down and lock up before our monthly Trust meeting. The usual guided tour, but in reverse: for here I stand at its far point, in the Blue Room, an elegantly long addition to the south-eastern corner of the original hillside villa, the Pluto of the little solar system of which Raymond of course was the Sun.

Naturally, I can’t render here the feeling this room always has for me, its sense of the past caught in the best of ways, not as in a museum or mausoleum but as if in a place of genuine transition, a place where time itself is annihilated or suspended—rendered irrelevant in whatever way: it hardly matters to explore or explain. I confess that sometimes when the day gets a little taxing I sustain myself through its desolations with the promise of an hour of solitude here in this timeless room, with a very dry sherry to help me remove the sour taste of the quotidian, and the familiar sound of one of the Master’s vinyl records from fifty years ago—my favourite is a Geminiani Concerto Grosso that has a little Vivaldi piece for castrato on the far side of the third disc as a bonne bouche.

It is the colour of the walls here, though, that would truly take your breath away if you could but see them (which you may, of course, during the advertised visiting hours: donations always appreciated since the place doesn’t maintain itself, as I’m sure you will understand).

We four Trustees simply wore ourselves out finding the right tone for the paint, and I imagine the city’s paint-shops were glad to see the back of us the day we realised we’d done it at last, we’d finally persuaded them to mix us exactly the right blueness of blue!

And when we got back to the Residence it was as if each brushstroke we began to make was reviving the entire house—as if all the scuffs and abrasions of time were being cancelled out, and we were back there thirty years before and more, all of us, when Raymond arrived at this house a handsome young man and the entire the world was young. When we were done, none of us needed to say a thing. We simply stood there. We’d travelled through time together: it was as simple as that.

I’ll tell you a little later about the trouble we had with the curtain material and how Semple got caught out when he had the fabric replaced on the rather lovely belvedere fauteuil over by the piano—we hadn’t taken the work of the sun into account, and you can imagine what happened next!

Pause, now, instead, before the pièces de résistance, the termini ad quem of our tour: the Medal itself, and, below it, framed, the Citation from the Committee. Of course, they’re not the actual medal or the actual citation, which are both in a bank vault, as you’d expect: but they’re such perfect replicas that even I, who have seen and held the originals—who travelled with Raymond to Stockholm, in fact, and witnessed his investiture—even I find myself catching my breath now for the sheer meaning of them, for the sheer achievement they represent.

For Raymond was the first in our little country to win the greatest prize of all, in a time of overwhelming excitement each of us remembers and remembers and remembers, and in which we all seemed suddenly to loom a little larger in the world, each of us, all of us—yes, yes, I know, people say I’ve let it come to mean too much to me, and Robert Semple reminds me from time to time—unnecessarily—that I didn’t actually win the prize myself. He also tells me to remember that, in a sense, the original medal and citation are themselves both replicas, too: all fashionable nonsense, of course, and really and typically irritating. Why he refuses to see the transformative, the redemptive nature of what Raymond achieved, the true, inner meaning of it, I simply cannot understand.

No matter: come away with me now, instead, through the little hallway and past the door of Raymond’s bedroom, with its sea view through the arch of the trees beyond its window to the sea and peaks beyond—elderberry, native honeysuckle and, much further down the hill, a big burly rata, each helping to form an exquisite frame for the view. Then, past the kitchen door—not because the kitchen isn’t interesting but precisely because it is, distractingly so, and would require a chapter to itself for justice to be done. Kitchens of all rooms in any house have the most potential for something that lies beyond nostalgia, Raymond used to teach us, and are places where one is most likely to find not just the pastness of the past at its most fully preserved, but that pastness at its most nearly available. I mean somewhere so close we might actually enter it. A portal, if you like. I’m talking Raymond-talk here, of course, as you’ll know if you’ve read his books.

Now: the dining room. Here, the eye is first drawn to the Henri II buffet against the eastern wall, with the remarkable Italianate walnut panel carving on its doors—birds, fruit, landscape, even the effect of clouds: authentic, I’m all but certain, and—like the Louis Quatorze sofa in the Blue Room—one of many such pieces from the Lawrence family estate as distinct from the various items Raymond picked up in his travels overseas. There’s the hand-painted lacquer Shoji screen we’ve just left behind in the Blue Room, for example (which we were told by a recent Japanese visitor in fact represents a brothel scene rather than just four artless geisha).

For all its magnificence, however—its wood like molten toffee—the buffet is not what I seek in the dining room. I seek Raymond. Not the actual Master in the flesh, alas, since not even art can bring him fully back, not yet: I seek Raymond in the flesh of paint.

And here he is, framed over the extinct old front room fireplace at 56 inches by 64, courtesy of Phyllis Button at her best, before the visionary period that signalled the onset of her dementia. The painting hangs here and not on the long walls of the Blue Room as something to confront the public: they enter, pause, look at the buffet and (always) ask whether it is real or not (meaning, of course, whether it is authentic), then how much it is worth (I’ve no idea but I conjure up imaginary figures to make them gasp), and then turn right and—well, here he is, here he is in glorious Technicolor.

In truth, though, in far better: in Phyllis’s sparkling, even shocking end-times style, with its splatters and scrapes of oil straight from the tube, oranges and reds and (of course) bright blue, his defining colour, smeared on the canvas as if she were trying to get straight from the medium or through it or even around it, to the man himself, to Raymond Thomas Lawrence—Nobel Laureate, Master, genius: martyr. It’s an extraordinary work, full of life and all the evidence you need of the way a work of art can show its artifice while at the same time transcending the strokes and smears of which it is made, and (even if only for a moment, even if only to particular eyes) make that impossible leap into life itself, hot, quivering and now.

And the oddity is (I am reminded yet again as I stand here before him) that the more she flung the paint on the canvas, and scraped and smeared at it with her knife and hands (brushes all discarded at this late urgent hectic potty stage of her life), the more nearly she seemed to make that leap: so that here we have a work of art which, at first glance, looks very nearly abstract expressionist in its mode, yet at second or third becomes very nearly representational, its chaos almost capturing the very man himself. And from behind—from behind!

For that is what is so mad, and so utterly inspired, about this portrait: it shows no more than the back of Raymond’s head, his veriest occiput, a smear left and a smear right giving a sense of the shoulders below, a wild plump dab of paint giving the nape, and then three or four greyish upward scrapes his back hair to the thinning crown, of which she takes care with a bluish flick of green, somehow: and, on either side of the big, gestural bonce thus confected, with cadmiums yellow-orange-red, a vegetal ear. Beyond and behind the right, the tiniest line of paint indicates something of his steel-framed spectacles. And it is he, Raymond, the Master, forever caught!

Like Michelangelo’s David, I said to him when it was exhibited: turning away, I meant, always turning away from the viewer. Michelangelo’s David? he said. It’s a bugger’s-eye view!

Vulgar, this last, alas, yes, yes, regrettably so: but it must be recorded because so very much Raymond, and Raymond it is whom I’m after in this account. My uncle, and in due course my adoptive father, too. I seek the very man himself.

Ah, Raymond, Raymond, Raymond—where are you? No idle question, this: it comes up every time I find myself alone at the Residence—which happens more and more often lately, I’ve found, given that the other Trust members increasingly make this or that last-minute excuse to avoid turning up for touring parties and for the board meetings we’re supposed to have here on the first Tuesday of each month, not to mention the occasional working-bee that I call. More often than not it turns out I’m the only one prepared to attend the former, and end up spending a solitary evening at home after all. Sometimes there are no apologies whatever and I find myself coming down to the Residence to find it looming above me closed and dark, and with absolutely no idea whether the others will eventually turn up or not.

Whenever that happens, there is the eerie business of feeling my way up the steps, and to the front door and, after the work of finding the lock with the nose of the key, pushing inside, lighting the place room by room and then turning back through the bright house and sitting and waiting at the oak dining table—Patience on a monument smiling at Grief, as Raymond would have said—until it becomes obvious that no one has remembered: or that indeed they’ve remembered all right but simply can’t be bothered.

Or worse, in the case of the appalling phrase Semple used when I made an acid phone call to him on one of these occasions and discovered him involved yet again with some silly little tart in his bed. Urgent Business Elsewhere, he said, with the woman’s giggles in the background. Well, I told him what I thought of indulging in that kind of business when he ought to have been at the Trust meeting, and that’s when he said the phrase in question. For Raymond’s sake, I said to him—come on! Can’t be arsed, he told me back. You can’t be what—? I said, unable to believe my very ears.

Now, here I am yet again with a deserted building to confront and the prospect of yet another wasted evening to be spent inside it. And, always on these occasions, that question—where are you, Raymond?—and the strange sense, whenever I’m standing at the top of the front steps with the wind blowing in my hair and my key tapping blindly against the plate of the lock in the darkness, that Raymond is inside the house, that when the door finally opens and I click the stiff brass light switch just inside and to the right—lo!—he’ll be sitting there like Jeremy Bentham in his stall at University College, staring back at me, waxen of head and tissue preserved!

Sometimes when this fancy takes me Raymond is as I first met him, barely forty and ruddy with health, his look sardonic, his purpose, as always, impossible to pin down. At other times, it’s as if he’s in his last months and crouched atop the elevator platform in his fauteuil roulant, as he used to call his wheelchair, his head and his hand going tick-tick-tick as was often the case in the final days. Once, as I fumbled the key at the front door lock, I was sure I could hear the buzz of the wheelchair elevator inside as it made its climb to the main floor, ready to greet me. With what?—would he be there at last on its platform, when I got the door open, would he be crouched there and waiting in his wheelchair?

And, of course, he wasn’t, and hasn’t been, and never is, and part of me knows he never will: but the feel of him is here, always, the feel of his colossal, overwhelming presence is everywhere as I push into the house and its darkness, banishing the world of enchantments with each click of successive brass light switches: till I reach the Art Moderne plastic switchplate of the Blue Room at last and expose for myself the final disappointment: that, once more, I have driven him before me and away.

He is nowhere. He is somewhere. He is everywhere.

I have paused, here, to take in again the pastness of the past, but now I turn back to the actuality of the dining room and the business of setting the papers before each place at the table. Order, gentlemen, please: ladies, too, Marjorie will always say indignantly, whenever she can be—well, whenever she can be arsed to be there, I suppose, to use Semple’s hideous phrase. At which objection he, Semple, always laughs like a hebephrenic: if, that is, he can be arsed to be present as well. Then, at some point, he will call someone or other a tit, and Marjorie will bristle and say, well, there’s nothing wrong with hers, and Semple will say once again that the word has nothing to do with breasts but comes from a Middle English word that means small and insignificant, and Julian will add, irrelevantly, that birds has derived by metathesis from brids—women, and hence brides—and Semple will say, There y’go, Marge, you’re a bride not a broad! And another monthly meeting of the Raymond Lawrence Literary Trust will have begun. Order, order please, gentlemen; we have business to do—ladies, too, of course, of course. Ladies a plate.

And indeed we do have business to do tonight, as you can see on the agenda that I place around the table. Item 1 involves money, an ongoing discussion past which, frequently, we fail to move in two or three hours. Item 2, related, involves the upkeep of the Residence and its surrounds, always a concern. Item 3, which I think I’ll move up to Item 1 in view of my latest discovery, refers to theft by visitors and an update, which I think will impress my fellow members, of my attempts to track down recent thefts.

Now, though, it seems someone is actually turning up at the Residence: a soft clump of a car door down on the drive and—yes, up the steps and through the door the first Trustee struggles, carrying her past around her in the clutch of bags and reticules that weigh her shoulders, wrists and hands: Marjorie Swindells, dabbing a hankie at what seems to be a perpetual slight cold (Semple assures me she’s a secret Catholic, since, according to him, Catholics always have colds).

A loud parp at her nose, and then:

‘Hello, Peter,’ she says to me in her defeated, resigned, slightly creaky private-girls’-school voice, and down the bags go, one by one, slumped on floor and chair and tabletop, and away goes the hankie in a quick tuck at her wrist. She straightens: ‘Well, what’s the problem?’ she asks.

‘I’ll tell you when the others get here.’ I prefer all the Trust to be present when it’s serious business. ‘But it is important.’

Now her face comes into the not-unsubtle light I have arranged over the table and I can marvel once again at the workmanship of it, her phiz I mean, the craquelure of tiny lines that comb her brow and upper lip, the cockling of her cheeks. In that process, even her ear lobes have developed sudden, abrupt little folds, as if beginning to close in on themselves, as if starting the business of rolling her up like an ancient canvas that is to be put away once more to allow a real, a still-youthful Marjorie to go on living and sinning. Or, possibly, to reveal no one at all: one never knows.

All nonsense, of course: here she still is, after all, caught in the unforgiving present like the rest of us, just come from the ladies seminary at which she plies her trade as a teacher of art history, drama and creative writing. Whatever that is, Raymond always used to say whenever the topic came up. Teach writing? he’d say. What d’you fucking mean, teach it? They don’t teach you how to shit, do they? Well, actually, they do, Raymond dear, Marjorie always used to tell him whenever he got to this point. They do but you’ll have forgotten. You can’t just let fly, you know, you’ve got to learn to aim at the pot. Fuck the pot, he’d always tell her. The pot’s the problem—

Why is she here; I mean, why is Marjorie Swindells part of the Raymond Lawrence Literary Trust? (In fact she’s not here at the moment, having just slipped off to spend a penny, as she puts it, tinkling distantly on his big old porcelain throne: whose craquelure, it must be said, rivals hers). You may take your choice of answers to the question of why she is a Trustee: (a) there was a long period many years ago when Raymond frequently took her to his bed—yes, that bed, the one in the front bedroom—and had sport with her: (b) she has a genuine literary achievement in her own right, a big, sad, first-and-only novel called Unravel Me, about (wait for it) a young woman who gets tangled up with a famous male artist. It is some years gone now, and nothing has come since—certainly nothing to rival the éclat of its Moment and the rather more than fifteen minutes of fame that followed.

I read it straight away, naturally—everyone did—and was dismayed, horrified, to see how good it was. I listened to the interviews that followed and marvelled—again, everyone did—at the disparity between the virtues of the novel and the cuckoo qualities of the person who had apparently written it. How did it happen, whence did it come, had it been written by someone else?—by Raymond himself, as part of some obligation about which we knew not, or as a joke whose punchline he would reveal in due course?

Time passed, though, and it became clear that there was no such course: and Raymond insisted, all the while, that he had nothing to do with any of the book, neither its composition by sleight-of-hand nor as the original of its Magus-like antagonist, Begg (this despite the generosity with which Marjorie described certain parts of that character in certain parts of her text).

Now, though, the slam of a car door, a call from outside, hulloo—and it is Robert Semple’s turn to arrive: gracious me! Here he is after all, swarming up the concrete steps to the front door, here’s his ugly-handsome face beneath the curve of his silliest affectation, a wide-brimmed brown fedora he almost never removes: and here is his tender, stepping, haemorrhoidal gait.

He stops dramatically a pace or two into the room and spreads his palms, his eyebrows raised: what’s up?

‘The paua shell ashtray’s gone. Stolen.’

‘My God—!’ His hand slaps his brow, his head goes back. ‘Raymond’s ashtray!’ He holds the pose, eyes shut tight.

Exasperating, of course, infuriating—really, I sometimes wonder about his commitment to the Trust. But there’s no changing things: his name is on the Trust document, Robert William Davidson Semple, along with those of Julian Howard Yuile and Ursula Marjorie Swindells. And, of course, along with mine, as Principal Trustee: Peter Edward Orr. I could easily do without any of them, to tell the truth (though perhaps Julian least, since he is harmless and has his uses), so that I might run the Trust myself. Semple in particular is a trial, in ways you’ve probably begun to pick up already. His poetry you’ll have already judged for yourself, I imagine, if you’re familiar with it. His other attributes—well, I’ll let you judge those for yourself, too, as they unfold themselves.

His connection with the Master?—as in my own case, from an early age, though not quite as early as mine: slightly post-pubescent rather than slightly pre-, and (I’m aware) with the same questions eventually raised as in mine: I mean questions to do with the price paid later in life for things gained earlier on. These are evident, one might say, in his behaviour, Semple’s I mean, most obviously in his frenzied rutting, of course, and also—but here comes Julian now, our fourth Trustee, pushing in through the doorway as if conjured by my naming him a moment ago: and here is Semple, turning to him and seizing his shoulder:

‘Come and see the missing ashtray!’ He points wildly towards Raymond’s bedroom.

Julian is mystified. He looks across at me.

‘The paua ashtray is gone,’ I tell him.

‘Shit—really? That was authentic—’

‘Authentic!’ Semple, bursting into florid, contemptuous, simulated laughter.

‘Well, it is,’ Julian said. ‘You could see his actual ash in it.’

‘Excuse me, it’s not his ash? It’s just his cigar ash? Where he stubbed his cigars out?’

‘No, but not everything in the Residence is, you know—’ Julian looks around. He gestures at a bookcase. ‘One or two of those books aren’t his, some of them are second-hand—there’s other bits and pieces we’ve replaced when things go missing.’

‘Exactly, right, and the ashtray’s the same, it’s just a paua shell he picked up off some beach somewhere—’

‘Yes, but I know what Peter’s thinking.’ Julian flicks a look at me and away. ‘We should value everything—you know, everything he touched.’

‘Christ!’ Semple turns away dramatically. ‘“Is He present in the wafer?”’ He really is getting angry now, and the theatrics are holding things in rather than the reverse. ‘I thought they sorted this shit out five hundred years ago—’

‘Hey, steady on.’ Julian is a Christian, of the garden-God variety: Semple likes to goad him. Where’s Marjorie got to?—we need her here, to play her customary role of scapegoat and victim: then the Raymond Thomas Lawrence Memorial Trust really will be in its full dysfunction. But Julian is on song tonight, it seems, and holds his own as the argument with Semple develops. It’s an old issue, after all, the nature of the Residence and how properly to remember the Master, and during the last five years we’ve all heard one another’s opinions on the matter.

By and large, on this issue, Julian and I are Catholics, if you see what I mean, and the other two are Protestants—in other words, two of the Trust feel that the old man is all around us, in everything, still alive, imperishable, and two of them feel—well, that he isn’t, that everything we have accumulated in this hundred-year-old villa on a lower spur of Cashmere Hill simply represents the life of the great artist who lived here for forty years and wrote many volumes of fiction long and short. Which view (I hear Julian now, arguing once more against this) runs quite contrary, surely, to what the Master himself wrote about most often: I mean the power of art to take us beyond mere nostalgia, as I’ve said, to the very past itself—

And what has Semple to say, once Julian has finished his defence of the Master’s presence in the ashtray?

He pauses. Then: ‘Don’t call him the Master, Jules, old boy, it’s bad enough Norman here calling him that.’

He means me, he is referring to Norman Bates, and I’ll leave the rest to you—and, anyway, here comes Marjorie at last, back from her feminine devoirs in the bathroom, the strap of her principal handbag over her arm and her makeup evidently brighter.

Semple is upon her straight away, eyebrows up and brow glistening and furrowed. ‘Have you heard the news?’ he demands. ‘The paua shell ashtray’s gone! It’s on the black market, selling for millions—’

She looks across at me. ‘You’ve dragged us across town for that? I thought we’d at least had a fire somewhere.’

‘Marjorie.’ Semple takes her fingertips as if wanting to dance. ‘Now you’re here we can vote. “The Master” or just plain “Mister”—?’

‘Oh, not that again.’ She pulls away. ‘You know I think it’s pretentious. So does Jules.’ She’s into her bags again.

‘Yes, but he’s started to use it. Julian here. He’s caught it off Norman.’

‘God, Peter, he was just a man. Raymond. Just a man.’

‘A great man.’

‘A great arsehole, come on, you know that—’

‘I’m aware of your views and you’re entitled to them.’ I’ve long ago learned to keep my temper on this topic, but it isn’t easy, it isn’t easy. ‘In my opinion and that of many others, he was a great man and a great writer. The proof is on the wall in there—’ I’m pointing towards the Blue Room.

‘God, if you knew him the way I knew him—that body!’

‘I remind you who I am.’

‘Yes, but you didn’t bonk him—or did you? Did you—?’

‘Yes, Marge, we all know you had in him in your boodoyer!’ This is Semple, of course: he loves this sort of thing. Julian leans against the molten walnut of the buffet, arms folded, waiting as Semple and Marjorie begin to argue yet again (‘Don’t call me Marge’, etc.). If only they were better writers. If only they were better people!

Was it Raymond’s last great trick—I’ve often wondered this—to appoint three absolute nonentities to his literary trust to take care of his reputation after his death: was this his last great joke? Did he think I was a nonentity, too, was he saying that, we were all nonentities to him? I asked someone this, once, a theatrical friend of my uncle called Basil Bush, and the man gave me a very untheatrical answer. No, it wasn’t because you’re a nonentity, the man told me. It’s because you’re so bloody difficult. Like father like son. I’m not his actual son, I reminded him. No, but nearly, the man said. And it shows, because you’re both complete and utter pricks. He doesn’t want anyone getting near the truth about him, he said, and he knows you won’t let them.

The old fellow looked at me hard when he said this. He knows you’re as mad as he is, he said. Madder. He knows you’ve got his DNA.

And I wondered, how much of the story, the full story, did he know?

Now, at last, the September meeting of the Raymond Lawrence Memorial Trust, properly notified and quorate: Hon. Chairman Mr P. Orr, Hon. Secretary Ms M. Swindells, Hon. Treasurer Mr J. Yuile, Order please—

‘Oh, shit, is there a meeting now?’ Marjorie has just noticed the papers set out before each chair at the dining table. ‘You just said it was an emergency.’

‘That’s the emergency, having a meeting!’ Semple. ‘Once a month, Marge, thought you’d remember once a month!’

For twenty seconds, the usual rattle of ill-tempered gunfire. Order, order—

We get through the prefatory nonsense—is it your wish—those for—AYE (Semple always very loud at this point, sometimes sustaining the note like a choirboy) those against, CARRIED.

There are no matters arising but under chairman’s business I am able to report the ongoing sale of unauthorised Raymond Thomas Lawrence memorabilia online—cheap bric-a-brac, more a hangover from the time of the award of the Prize than a real and ongoing threat, but crass and irritating all the same: for example, a line in garden gnomes made to look like the Master—the Master sitting fishing, the Master as Rodin’s Thinker, even (most lamentable of all) the Master as the Manneken-Pis. Appalling, upsetting, infuriating: but, according to our legal advisors, untouchable, since we’d lose more if we sued, apparently, than we might gain. And, as I said, this particular phenomenon does seem rather to be fading out.

‘You’ve told us all this before,’ Semple is slumped forward, his arms along the tabletop.

‘True,’ Marjorie works a moist refreshing tissue at a reddening septum. ‘Next business please.’

‘We haven’t got to the business proper yet,’ I tell her. ‘I’m still doing chairman’s business.’

‘All right, do that,’ she tells me. ‘Come on, chop-chop.’

‘Roof repairs,’ I tell them.

‘Isn’t that Item 2 Upkeep?’

I remind Julian I’m still reporting from the last meeting. ‘Eric the handyman’s had a look at the roof,’ I tell them, ‘and he gives it a year.’

Pause.

‘And then, what?’ Marjorie demands. ‘It all falls in on us?’

‘And then it needs repairing,’ Julian says.

‘And then it needs replacing,’ I tell them.

‘Oh, shit. Let’s forget about that, then, what’s next?’

We move on to the agenda proper.

Proposed from the chair: That in light of today’s theft, Item 3 Security be moved to Item 1: CARRIED nem. con.

Once it gets there, though, the perennial impasse returns.

‘I can’t believe we’re discussing a fucking paua shell ashtray,’ Semple groans. ‘Who cares if some prick’s nicked a paua shell?’

‘It’s not just a paua shell,’ I remind him.

‘We’ve discussed this before, aren’t we rather thrashing it to death?’ Marjorie asks. ‘Next business please.’

But the next business is Financial, and there, the same issue threatens to come up again, melting—order, order—into Item 3 (as it is now), Upkeep.

Whichever item we deal with, of course, it’s about the same thing, even I have to recognise that: the need to find money against the perennially rising cost of running the Residence and the fundamental, ineluctable fact that, even without our having spent a dollar of it, the Trust’s endowment capital has become relatively smaller and smaller as each year has gone past. And against all this, the need to keep alive the authenticity, the integrity of the venture. Its purity, even: even its spiritual aspect.

Whenever we discuss these things, as I’ve said, Julian and I are always for the latter, and Semple and Marjorie are always (in effect) against: meaning that they want to start selling some of Raymond’s objets to pay for upkeep, while Julian and I don’t want to sell anything at all. They want to represent Raymond’s life with bits and pieces from second-hand shops, imitation antiques or even rough approximations, used books by the carton-load from the back room of the university’s bookshop, knives, forks and spoons from Bargain City out by the airport, and so forth. Julian and I have always held the line against these proposed atrocities, and for authenticity.

And here, at this evening’s meeting, the perennial impasse, presenting itself yet again. Semple starts the show:

‘Every single problem on this’—he taps his agenda—‘would be solved if we cashed the place up.’

‘There’s no motion on the table.’

‘If we cashed up, it wouldn’t matter what they nicked, they’d be nicking crap anyway, we’d just replace the crap with more crap. If they gouge it we’d, you know, use wood-filler? If they keep on gouging it we’d replace the whole item from a junkshop. It’d all be crap.’

‘I have only one thing to say about this.’ A pause, as I look around the table. ‘Mabel Carpenter.’

‘Oh, fucking Mabel Carpenter. Not her again. Christ, she was dreary.’

‘Yes.’ Julian. ‘Some of her stuff’s unreadable.’

‘All of it’s unreadable.’

‘She was a great writer, though,’ Marjorie says.

‘Oh—no doubt about that, she was a great writer all right.’

‘No doubt about that at all.’

‘Her Memorial Residence is a disaster,’ I remind them. ‘We all know that.’

And it’s true, both that the Residence of the late Mabel Carpenter—she whose fiction brought Dargaville to the world—is a joke, and that we all know is so. When it was first opened we had a look at the place, Julian and I, driving north after a conference in Auckland at which the pair of us represented the Master late in his life, when he was too ill to travel. Naturally, given his condition then, we had thoughts of what might soon—and now, alas, has—come to pass: I mean how a writer’s home might most properly be turned into a memorial residence once he has (as Raymond used to put it) passed on to the great whisky decanter in the sky.

Not like that! the pair of us chortled happily as we drove away from Mabel’s Residence afterwards. It was her house all right, I mean it was one that she had lived in: but for years after her death it had been rented by civilians (as Raymond used to call the inartistic), and there was not a thing she’d actually owned in it once her memorial trust decided it was time to commemorate her, nor anything very much to guide them in their sad little reconstruction.

A desk very similar to one Mabel might have written on is a line I remember—with laughter—on a notice tacked to the wall above a very ordinary table that had been sanded down to nothing, no past in it, no life. A bed typical of beds of the period was another. The pièce de résistance—the nearest they could manage to the real thing, the nearest to achieving, for the literary tourist, the true and authentic moment—was a clothes-wringer in the outside laundry, certified to be authentic on a nearby placard, though described as a mangle all the same. Mabel’s mangle, we came to call it, and we were quite clear that, when the time came, the Raymond Lawrence Memorial Residence would do better, far better, than that.

Naturally, I remind the meeting of all this. We mustn’t get caught in Mabel’s Mangle is my concluding line—rather a good one, I can’t help thinking.

There is a pause, and then Marjorie continues as if I haven’t even spoken!

‘It’d have to be good-looking crap,’ she’s telling Semple. ‘It’d have to look almost the same as the stuff we’re talking about selling.’

‘It’s not stuff and we’re not talking about selling it,’ I remind her. ‘There’s no motion on the table.’

‘You mean if there was, you’d discuss it—?’

‘If it had a seconder.’ I look across at Julian. ‘Then I’d have no choice.’

‘All right.’ Semple. ‘I move we sell the Steinway.’

‘Oh, not the baby grand,’ Marjorie says.

‘I think’—this is me, feeling my way towards a deferral—‘I think it’d be better if we addressed the principle first rather than the particulars.’

‘My motion’s on the table, fuck it—’

‘No, it’s not, there’s no seconder.’

Semple looks at Marjorie. ‘Come on, Marge,’ he says.

‘Ask somebody else. I don’t want to sell the baby Steinway. And don’t call me Marge.’

‘It’s worth more than all the rest. It’s worth more than the entire house and garden. It’s worth hundreds of thousands. It’s a fucking Steinway, for God’s sake, with art casing, I don’t know how it got here in the first place—’

The Steinway is in the corner of the Blue Room, covered in framed photographs and with a large table lamp on it. It’s one of several items in the Residence obviously with some monetary value, though (it has to be said) not necessarily as much as Semple and Marjorie would like to think. Though they don’t realise it, I’ve had it valued, and found it would bring in about fifty thousand local dollars according to when and where it was sold and by whom. Overseas, of course, it would be a different matter, sold overseas it would fetch rather more. But then one would have to get the piano overseas in order to sell it, which would cost all we might realistically sell it for once it was there. Checkmate: and, in some ways, the history of our little country in a single proposition.

Marjorie, meanwhile, is casting around for alternatives. ‘That thing.’ She’s pointing at the carved buffet behind me. ‘Let’s sell that.’

‘The Henri II buffet?’ Julian asks. ‘You’d have a job replacing that, you’d have a job getting something cheap that looked like that.’

‘You’d have a job getting it out of the house.’

‘It’d have to be authenticated first,’ I remind them.

‘What about the berber rug, then?’

‘No,’ I tell them. ‘The berber rug is off-limits.’

Mr Semple’s motion that the Trust sell the Steinway baby grand piano lapsed for want of a seconder.

Ms Swindells’ motion that the Trust sell the carved buffet lapsed for want of a seconder.

Ms Swindells observes that the answer is to increase visitor numbers. Mr Semple expresses reservations.

‘You must be fucking dreaming,’ he says. ‘How are we going to get more of the bastards in?’

‘How many did we used to get?’ Marjorie asks me. ‘You know, in the good old days?’

‘Two or three hundred a month. More. Admittedly a while ago—’

‘Admittedly ten years ago,’ Semple says. ‘When he was still famous. Christ, when he was still alive—’

‘Yes, but—’ Julian. ‘We—’

‘They used to come here to get a sight of him drooling in his fucking bath chair. Ray. That’s the only reason they came, that’s why we got so many people through, the old boy was still around to gob in front of them.’

‘But—’

‘Yes, but even so, show me the literary residence in the country that ever got—’

‘How many literary homes are there—?’

‘Show me the literary residence anywhere—’

‘Yes, but—’

‘—that has consistently made a profit—I mean a meaningful profit, not just pocket money.’

I sit back.

Marjorie squirms her mouth. ‘Yes,’ she creaks at me. ‘That’s all very well, Peter, but you’re telling us yourself, dear. You’ve brought it up, you’re telling us we’ve got a crisis. Item 2, Financial crisis.’

‘A problem. A challenge.’

‘Yes, but’—Julian at last—‘it’s not just visitors, they don’t bring in that much, for God’s sake, they never have, we didn’t ask for anything at all for a long time and what do we ask for now? A voluntary contribution that hardly anyone actually makes.’

A pause.

‘True,’ says Marjorie. ‘We’ll have to start charging them to get in—’

‘Then nobody’ll come,’ says Semple. ‘End of story.’

‘But we’d have to charge a hundred dollars a visit to get anywhere near what we need.’ Julian turns to me. ‘What needs doing?’

I look at my list. ‘We pay quarterly rating, the phone, electricity—’

‘Well, fuck the phone for a start.’ Semple rocks from cheek to tender cheek. ‘Who needs a fucking phone when there’s no one here most of the time?’

‘Robert, darls, don’t tilt back like that.’ Marjorie. ‘These chairs just won’t take it anymore.’ Then (to me): ‘Maybe they need replacing, too—the chairs?’

Proposed Mr Semple, that the telephone be disconnected forthwith, seconded by Mr Yuile: carried nem con., Mr Orr to action.

What else?

‘The guttering needs replacing—’

‘It needs placing, there isn’t any at all round the side—’

I stick to my script. ‘The garden. We’re down to one gardening lady now. Val—’

‘How many did we used to have—gardening ladies—?’

‘Back then? Seven. But we didn’t pay them. Deciding to pay them was a mad idea. We were paying four at one stage—when those Austrians came and made that documentary we had four gardening ladies on the payroll—’

‘Yes, but doesn’t it look spiffing, in the doco, I mean—the house and the garden—doesn’t it look spiffing—? Summertime, and all that—?’

And now we sit for a moment, each of us, and think just how spiffing the Raymond Lawrence Memorial Residence really did look in the high summer of 2001–2, when an Austrian crew of astonishing seriousness came over and filmed Raymond pottering about among the lacecaps and the agapanthus. He refused to wear his partial upper denture for the actual interview and consequently looks like Klaus Kinski in Nosferatu, with just the two eyeteeth poking down on either side of his mouth. A section of this documentary opens the standard tour of the Raymond Lawrence Residence, which begins downstairs in the garden room with a closed-circuit showing after the signing of the Visitor Book, and then proceeds upstairs via the elevator: when the elevator is working, that is.

‘Oh, and the elevator,’ I remind them. ‘Still not working.’

‘It needs replacing,’ Julian says. ‘To tell the truth—doesn’t it? Isn’t that what’s wrong? The whole bloody shooting-box? It’s Apollo 11 technology, it’s another age, it doesn’t work anymore—’

A pause. They look at each other, Marjorie at Semple, Semple at Julian, Julian at Marjorie.

Suddenly Semple slams forward in his seat.

‘Fuck it,’ he says. ‘Let’s just close the place down.’

He holds the pose, looking around at us one by one, then pushes back truculently and waits with his arms folded. Julian looks at me, and I look at Marjorie. This time Marjorie looks at Semple.

‘We can’t close it down,’ Marjorie says. ‘Can we—?’

‘Got a better suggestion—?’

‘Well, we just can’t—’

‘For Christ’s sake!’ Semple slumps forward, his palms on the tabletop again. ‘It’s like what Jules just said, it’s another age—it’s not now we need to think of, it’s ten years’ time—twenty.’ He looks around. ‘Kids don’t read books anymore, they don’t read anything—what’s Raymond fucking Lawrence mean to them? The youngest people that come through the Residence are fifty-something. Readers are dying and illiterate cretins are being born—’

An awful silence in the room.

‘I mean, let’s stop kidding ourselves.’ He looks around, but not at any one of us in particular. ‘Let’s stop trying so hard. It’s the old, old story and it’s caught up with us at last, so let’s just face it.’

A slight pause: Marjorie looks at Julian, then at Semple. ‘I’m afraid I’m not quite sure what exactly you’re talking about, Robert, dear,’ she creaks at him. She looks at me. ‘Any idea?’

‘He means we’re past our use-by date.’ Julian. ‘That’s what you mean, isn’t it—?’

‘We’re irrelevant.’ Semple’s voice is so quiet it’s disconcerting: I don’t think I can handle him sincere. ‘We’ve got the population of, I dunno, Boston?—a city, I mean, we’re the size of a city—’

‘We’re a city-state—’

‘No we’re not a city-state, we’re not even good enough for that—Athens was a city-state, Singapore’s a city-state, we’re not anything. For Christ’s sake, listen to me, I’m trying to say something important—’

‘Listen to you!—we’ve been doing nothing but listen to you all evening, for God’s sake—’

‘Order—order—’

‘Oh, order yourself, Peter—’

‘We’re so fucking small, we’re smeared across the country like Vegemite, we just haven’t got the resources, we never have, and we tell ourselves it’s not like that anymore, we tell ourselves Ray took us out into the world and we’ve come of age—it’s not true, it’s all bullshit, it’s just pretending. This place is just pretending—’ He taps the tabletop with a fingernail. ‘If it wasn’t, we wouldn’t be talking about closing it down—’

‘You’re the one talking about closing it down—’

‘We wouldn’t have to grovel for support all the time, we wouldn’t be talking about money all the time, we’d be lying around talking about art, we’d be endowed by some big corporation, we could have guttering with goldleaf on it and a helicopter pad out the back—we could even have writers in residence, the way we’re actually supposed to but we don’t, because—guess what, we’ve got no money to pay them—’

‘Robert!’ This is Marjorie: she’s sitting back in her chair with her eyes fixed on him and a tiny smile. ‘You’re being sincere!—I quite like you like this, I can almost see what all those teenage trollops see in you—’

Suddenly, Julian leans into the discussion. He shifts about and begins to speak to the surface of the dining table.

‘With great reluctance—’

‘Here we go,’ Semple sits up.

‘Shut up, Robert.’ Marjorie is looking straight at Julian.

‘—I’m moving towards your position, Marjorie.’

‘It was my position first—’

‘Shut up, Robert—’

Julian flicks a look at me. ‘Sorry, Peter,’ he says. ‘I’ve given it a lot of thought. We know some of the furniture’s worth thousands, and the books.’ He sits back and folds his arms. ‘I move that the Trust affirm the principle of selling property items to fund upkeep.’

A stunned pause. I stare at him. I couldn’t be more shocked, I really couldn’t.

‘Seconded.’ Semple. ‘Well done, Jules.’ He slaps his palms together a couple of times.

‘Come on, Peter, you have to hold a vote now—’

‘Wait on.’ My mind is racing. ‘I don’t think it’s proper to the item.’

‘Bullshit. You’re making that up.’

‘What item are we discussing, anyway?’

‘Ah—one. Security. I don’t think it relates to security.’

‘No, we’re on Item 2, aren’t we? Upkeep?’

‘That’s no longer Item 2, it’s Item 3, I think.’

‘Then we’re on Item 2, money—?’

‘We’re still on Item 1, security.’

‘He’s stalling.’

‘I’d like us to discuss this,’ Julian says solemnly. He’s not looking at me. ‘It’s where we’ve been heading for years—well, at least five years. We should face up to it and sort it out.’ Now he looks at me. ‘I’m not particularly in favour of it, Peter, don’t worry, I just think we ought to thrash it out.’

A pause. We all sit there, breathing hard at one other. I stare at him. How could he? How could he do this to me? Julian, of all people?

In due course, it comes to its end, this latest meeting of the Raymond Lawrence Memorial Trust, with its customary sense of dissipation, its bickering and repetition, its sheer inartistic ennui. Each meeting wears me out, each meeting leaves me with the sense of having been the only adult in the room. I watch the others descend the concrete steps and depart through the trees to their cars. They feel so far from me, so little a part of Raymond and what it was that he stood for: yet again I wonder just what was he playing at when he appointed them? And now they want to sell him up, to wrap up everything he was and everything he believed in and give it away.

Oh, don’t be so melodramatic, Marjorie told me when I said as much just now, towards the end of the meeting. It’s the only way to keep the old place going! So it is, I told her: but will it still be the old place once we’ve done it? And where will he be then, what will we have made of him?

That, of course, is the point. But do they understand that?

Outside, I wait at the foot of the ten concrete steps that reach down from the front door of the Residence, and listen to the other three of the Trust disperse in the night. Their cars are down by the garage: a car door slams. Come on, I can hear Semple calling. Shake it up. Then: What’s that?

I’m spellbound, trying to catch what they’re saying. Is it about me? There’s a slight wind, off the sea, enough to stir the leaves. Hard to tell. Once, standing here in the dark after a meeting, I heard Marjorie say, No, he sleeps in the Residence, and the quack-rattle-and-bark of their laughter. Now, here it is again—has she said it again? No: Semple instead: Well done, he’s saying. Then: bang, from another car door, and a moment later an engine starts up.

I creep forward, the smell of pine resin and eucalyptus gum in my nostrils, to look through the foliage as the Trust members reverse down the drive en convoi, the sweep of headlights creating a ripple of movement in the bushes and the trees around the driveway. I can see Julian waiting down there for the silly red MG or whatever it is that Semple affects: a pause, as he works his wheel this way and that, and then off he goes, blaring down Cannon Rise. Now Marjorie’s Mazda Familia moves away behind it.

Well done—it stays with me, up the steps and through the doorway and as I close and bolt the door. The thought of what they want nags at me as I check the house and turn out its lights.

Marjorie’s line about my staying the night here at the Residence has its own unintended irony since, unknown to them—to anyone—I frequently do just that, and intend to do so again tonight. Never on Raymond’s bed, naturally, but (almost as great a desecration) on the long sofa in the Blue Room. I know I’m taking a liberty, but I do it simply for that moment when I wake into the room each morning as it slowly illumines. Especially at dawn in midsummer, the slow flush of daylight turns it into a sanctum sanctorum and an annunciation of his presence: a confirmation that, in some form at least, he is still here, still with us.

More than that, there is a moment, just once a year, when the first light strikes exactly on the Medal itself, and holds it, and seems to linger there: but, then, of course, it slowly moves away, having made its statement—having held me as well, having utterly held me in its moment. Just the two of us. The meaning of him, and of his life. And I, his child and servant: in truth, his creation.

Now, I turn the last light off. I know the house blindfold. Through the little hall—there, the tight floorboard creak that is always two steps in: I tread it and stand, reassured, in the doorway of the Room, looking for the familiar shapes in the dark, smelling that familiar blue smell. Inviting him: is he here?

Raymond, I call to him.

Usually it scares me when I do this, as if I’m listening to someone else who’s inside me and who shouldn’t be there, who shouldn’t be.

Raymond?

There’ve been moments when I’ve done this and really felt frightened but knew he was there somewhere and turning away from me, always turning away: once, I called his name in the dark and a moment later heard the floorboard creak behind me as he moved off, creeping from me, stealing off into darkness.

Raymond?

Raymond—

Tonight, though, nothing: I know there’s nothing there. The Residence sits around me, inert, harmless, unthreateningly in the present tense, devoid of purpose, oblivious of danger.