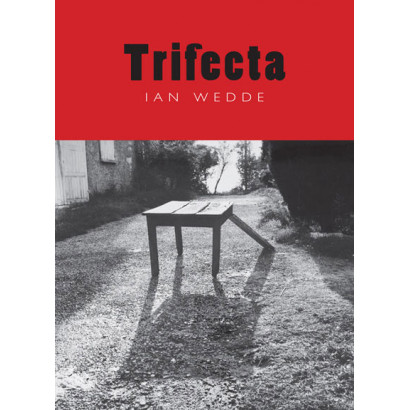

Trifecta

From: Trifecta, by Ian Wedde

Chapter 1: Mick

Every day the same I’m waiting for him at the bottom of my street, rain or shine. Flat tack around the corner pushing that old wooden toy lawnmower towards the corner dairy where Mrs Patel will be singing along to a CD, waving her fingers loaded with rings. The others come after in dribs and drabs, mooing and giggling. It’s a highlight in their day. The one they call Push has the edge on them despite the wooden mower. What happens if they get in front of him can be entertaining or ugly depending on your attitude to the mentally feeble.

It’s pissing down but I let Push go first as usual. His minder’s keeping up okay but it’s an effort, the so-called New World Syndrome. She’s got the wooden lawnmower to thank for her daily workout. She gives me a wave and a smile stretched to its limit by exertion. Push rams the mower into a blocked storm-drain grille and begins to yell when it gets stuck in the flood. He yells as if someone’s tearing his toenails out with pliers—right up there at the top end of what any listener could handle, shrill, ear-splitting, with fragments of word-shapes hurt past recognition. You can tell what he was like as a kid. He still is. But his age comes as a shock when you get close enough to his weepy little red eyes and badly shaved top lip, the few snaggly teeth sticking out under it.

To her credit Push’s hefty minder goes in over her ankles getting the mower past the soggy dam of leaves and paper and back on the footpath. On they gallop around the corner by the tinnie house. There’s a hint of aromatic relaxant in the air. Bit early for a smoke. A couple of tuis are trading insults in the Norfolk pine, one of them sounds like a car alarm, the other like a doorbell. They could be courting. Excited dogs are yelping up in the misty Town Belt, they could be having fun. The rain drifts down off the hill with a smell of rotting foliage in it. Behind me the rest of the crew are making good progress, hooting and shrieking. The street’s sounding like the Amazonian rainforest as the dawn chorus heralds a brand new day.

Mrs Patel is an exotic creature. First thing in the morning she has a dreamy look as she sings along as if some pomaded Bollywood matinee idol with drowsy eyelids is gliding into the shop instead of Push with his two-dollar coin. Her son, an earnest high-school lad with glasses, hands over the two-dollar lolly mixture with one hand while dealing to the till with the dextrous fingers of the other—a virtuoso performance he’s been perfecting ever since he had to stand on a box to see over the counter. I’ve watched him every ka-ching of the way. He’ll be off soon, finished the early morning shift. In the evening he’ll be back at the till doing his homework under the counter. I wonder if I’ll be around on the day he discovers he’s stuck there and begins to scream like Push in the storm-drain.

I get in quickly for my smokes. He knows the brand—his fourteen-year-old moustache flinches off his teeth in a smile but his eyes are on the doorway where the halfway-housers are jostling for pole position. Outside is the elderly, gloomy one who won’t go into the dairy so wanders into the road and stops the buses while his minder gets him smokes instead of lollies. It amazes me that they let these people smoke. It also amazes me that someone short on brain function can be sad. Push has already rattled off down the hill with his minder puffing behind. He’s on his way around the block homeward bound steering the wooden mower. That must be all the exercise he’ll get on any day, poor little bugger.

I don’t know what it is about the predictable detail of these morning rites that’s fascinating, given how nasty boredom makes me.

‘Jesus, you’re a nasty bugger, Mick!’ That would be my sister Veronica—Vero for short as in truth. She bores me witless. Her conversation is like do-up wallpaper, no sooner chosen than in need of replacement. Whereas Push’s morning gallop down the home straight, the huffing and puffing field that follows, and the erotic sound of Mrs Patel’s sing-along do not. Bore me.

My even more boring brother Sandy would haul out his tattered lecture notes at this point and bore me with the doctrine of, quoting someone, ‘man as an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun’. He means culture but what I see are spurts of endorphic excitement firing up the neurotransmitters all the way around the block and then back to the crooning catatonia of the halfway house where the liberated-from-culture zombies get re-zonked.

I don’t know either what it is about pulling the cellophane off a fresh packet of smokes and opening the top on that neat arrangement of filter-tips, but my spirits lift every time I do it. It’s the small things, the small things, the little symmetries. The sense of disinterested order. Another one is the blackboard breakfast sign outside the Cambridge. It never changes. One smoke gets me down the hill and across Kent Terrace at the lights by Super Liquor. The universe is an orderly place that keeps the essentials within reach.

My newspaper’s available at the Lotto shop by the pub where even the obsequious owner’s inquiry about my intention to buy a ticket (or not) is predictable.

‘Jackpot’s up to five mill?’ He’s holding my newspaper change back as if I might be amused. Also he’s speaking in questions as if that’s more friendly. Believe me, he’s looking down the once-too-often barrel. One day I’ll tell him what I’m capable of doing with that kind of money. But yesterday, today, tomorrow, my change is the price of the day’s first coffee.

‘Have a nice day?’

I intend to. Now give me the fucking change.

The backpackers who rest up at the Cambridge in preparation for their next Kiwi Adventure bus trip sometimes risk the dining room. A few are moving thoughtfully along the breakfast buffet’s chafing dishes. Over at the counter Nancy has that patient expression she gets when she’s measuring their all-you-can-eat expectations.

‘Mick.’

‘Nancy.’

There’s that whiff of Listerine PocketMist on her breath, Jameson’s under. I find it cheering on a rainy day like this, as I do Nancy’s smile which this morning seems false.

Some mornings I can almost hear my brother Sandy’s encouraging tone as he lectures his students about social distinction, cultural capital and status anxiety. On the rare occasions we phone he talks to me as if I’d booked office time with him. I like my coffee thin, black and stewed, from the decanter. I like my fried eggs centred on a piece of toast. I like to have my newspaper open on the table to the left of my plate. The best table is the one where the paper gets plenty of light on it. On sunny mornings this is by the window. Today it’s in the far corner booth with a wall lamp to one side. I keep my reading glasses in a hard case that makes a good loud noise when it snaps shut. It makes the backpackers jump. Yes, I’m like that. In Sandy’s world all this would mean far too much and he’d know far too much about the meaning.

Nancy’s insincere smile means she’s got something on her mind and that she’s going to tell me about it. And it means she already knows my breakfast order. So what? Unlike Sandy I’m not compelled to go deeper. She’s known what I have for breakfast ever since she started work here which was after the refurbishment five years ago. Do I miss the smell of cigarettes and lard? And at least a generation of beery farts around the bar stools beyond the dining room? I like Nancy’s aroma better. It’s homely, apple shampoo or something on top of the breath freshener and the Irish, and I also like it when she sits down beside me for a quick chat. She pats my hand to emphasise what she’s saying.

She’s read about my house in the paper, page two. The funny square red one.

I ignore that. Her youngest daughter’s pregnant again, number three. Nancy reckons the girl’s got some kind of hidden attractor that sucks blokes in and chucks them out. They never stick around longer than the first trimester. Sandy would have some kind of cultural explanation for that but Nancy and I know it’s evolutionary biology at its purest.

‘Hell’s teeth, I dunno, Mick. “The condom broke.” What was the dope using, Gladwrap? The one before this she said she believed she was in the safe zone, monthly-wise. Believed. What does she think she is, a Catholic? This last one was a bike courier.’

‘Express delivery.’

‘Probably kept his helmet on, he was out of there that fast.’

‘You’d think those tight shorts might do the trick.’

‘Clearly did. Another cup?’

‘Drop the sperm count, I mean. Yes please, Nancy.’

Probably the girl just likes having babies and likes athletes to have them with. I don’t say this to Nancy because she knows it already. She probably liked having them herself and with athletes for all I know but I don’t say that either.

When she puts my second cup down, Nancy pauses.

‘What?’ I ask.

She’s looking at me, so I take my glasses off.

‘Nothing.’

Glasses back on. I read that Real Deal helped bury a Gold Coast hoodoo for veteran trainer Corker Wood when she won the Magic Millions Classic across the Taz on Saturday.

Halfway across the room, Nancy turns and comes back.

‘That house of yours,’ she says.

Here we go.

I keep the glasses on. Wood’s filly pulled down $2 million for that race. Gundy Boy paid $31 in the MM Cup. Win some, lose some.

‘Never mind,’ says Nancy.

If I’d wanted a housekeeper let alone a careless one like Nancy’s daughter with three bastard brats I wouldn’t be sitting where I am now. And Nancy wouldn’t be stamping away with smoke coming off her. A burly, red-haired bloke in complicated shorts is feeling the heat of Nancy’s glare on his neck as he tests the capacity of his breakfast buffet plate. His ears begin to redden like the sky above bushfires in his native land. I’m no more responsible for the spark that just lit Nancy’s tinder than I am for the Black Saturday fire that nearly roasted British General four years ago, $10 at Flemington last Saturday, fuck it.

Nor am I responsible for the newspaper’s keen interest in my home. The item on page two has Sandy’s territorial piss all over it. Vero’s too probably, if she could aim straight—the house is on her Heritage Trail.

Let’s see, what would I rather live in, my own home, an architectural icon, or a heritage site? Nancy’s expression on her fourth return this morning adds another option: a house with four empty bedrooms and one selfish prick. She plonks my plate of eggs and toast on the table.

‘Don’t let them get cold.’

‘Thanks, Nancy.’ I’ve no idea what she means by that. None whatsoever. I have less trouble getting the hang of the newspaper article. Not the meaning of the words on the page, their easy-to-grasp account of one of New Zealand’s modernist masterpieces, its ‘austere elegance unmatched in post-World War Two domestic architecture’. Rather, the meaning of why the account is there on page two at all. Together with the all-too-familiar image of the coloured squares and rectangles attributed to the influence of Farkas Molnár. In ‘the literature’. Or rather, to keep it simple, the meaning of why I’m still there in the ‘neglected’ masterpiece. Why, why, why am I still there? Why is the place falling to bits? Where’s the furniture gone? All those fucking knock-offs of Marcel Breuer and other cultural icons who wouldn’t know a comfortable chair in which to jerk off if they saw it by the light of their spindly anglepoise lamps. Questions, questions, questions flooding the mind of the curious young person today. This is what the words mean—Sandy might as well have drawn a map for culture vultures and stuck an interpretive text on my front door. Chucked up a website. Or got a cultural petition circulating among professional architectural cognoscenti who have no business knowing let alone caring where or how I live. In the house that’s as much mine as theirs. My brother’s and sister’s, I mean. More, if you take into account the fact that I actually live in the fucking thing.

The fork that lifts egg to my mouth is trembling and a blob of yolk falls on the item about Maestro’s bruised heel. He’s not being entered for the Trentham Telegraph. His trainer Jim Tell reports, ‘I took him to a lovely fresh grass paddock on our new Cambridge property and he walked to one side and introduced himself to the horses in the adjoining paddock then introduced himself to the horses on the other side then mooched to the middle of the paddock and started grazing. He announced that he was in town and left it at that.’ Now that’s a beautiful piece of writing, accurate, vivid, evocative, if a little anthropomorphic, no hidden meanings just plenty to think about, and it leaves Maestro where he may safely graze in his home paddock.

‘Where are you calling from?’ I can tell from the overconfident timbre of my brother’s voice that he’s shitting himself. Perhaps he thinks I’m really in Phuket throwing trust funds at whores.

No, he thinks I’ve read the paper.

‘Payphone at the Courtenay Place TAB.’ It’s the truth but Sandy’s silence says he thinks I’m winding him up.

‘What’s the matter, Mick?’

‘And a very good morning to you too, Sandy. Professional intellectual track not too heavy for you today?’ I can hear the air whistling in and out of Sandy’s nostrils. There’s that funny glottal click as he swallows. ‘Still the odds-on favourite, Sandy? With the young crowd?’

‘What do you want, Mick.’ He says this as though it isn’t a question.

You can’t say I didn’t try. ‘I was hoping you could help me with a conceptual matter, Sandy. If you’ve got a moment.’ Nostrils, glottal clicks, and other sounds that suggest Sandy’s trying to get dressed with a cellphone between shoulder and ear. ‘Tell me if this isn’t convenient, Sandy.’

‘I’m at the gym.’

‘Is that convenient or inconvenient?’

‘Just tell me what you want.’

‘See, here’s the thing.’ There are certain expressions Sandy refers to as ‘memes’—he’s too much of a snob to pretend he doesn’t despise them.

‘The thing.’

‘Yes, Sandy, the thing. See, there’s this horse I think’s going to hit his straps any day now, he’s called Maestro, beautiful young chestnut thoroughbred, he’s got a sore foot at the moment so he’s been pastured, you know, allowed to stay at home for a bit, at home, Sandy, he’s a happy animal, bit anthropocene of me, I know, to say that, given that he’s been bred to entertain me and with any luck restore my fortunes, but leaving that aside, do you have any thoughts at all about the cultural dimension of an animal feeling happy and at home, Sandy? I’ve pretty much got the evolutionary aspect sussed, not to mention the endorphic happiness produced by a good feed of grass, but I need help with the wider social and cultural aspects, your field I believe. What’s your advice? Think the happy horse is worth a punt?’

‘Shut the fuck up, Mick, and stop wasting my time.’

‘No, Sandy, you stop wasting some poor young star-struck arts page reporter’s time getting my place plastered all over the paper, you miserable prick.’

‘Our place.’

I hang up. I for one have no doubt that Jim Tell is doing the right thing by Maestro. That horse will be happy and ready to hit his straps when the time is right. A runner’s high will be his reward when the neurotransmitters kick in over the last furlong, and my payoff something not dissimilar.

I’d been in such a hurry to get from my breakfast to the phone at the TAB I’d missed out on my after-breakfast smoke, so I step from the neon glare into the murky rain outside and light up. The usual deadshits are hanging about. The only reason I can come up with is that they hope to catch the eye of someone who’s just struck it lucky or exercised their finely tuned powers of odds analysis, whichever is most likely at the time. Alternatively the smelly, wheedling folk are there because this is a magnetic field of bad luck into whose orbit those convinced they are steered by rational thought are drawn. I give the young dude in the filthy sleeveless puffer jacket a cigarette. The old ones can get fucked, they’ve had all the chances they’re going to get. It’s not conversation I want but my Sandy-agitated ticker is still thumping away so I’m willing to be asked a friendly question.

‘Can you hear them? They’re under the ground. There’s thousands of them. The tiny burning Bibles.’ The dude’s cheeks disappear into his face as he draws on the smoke I’ve given him. His eyes have the endearing, personable look of someone whose moral dynamo is innocently grit-free. The answer to his question is no, I can’t hear the thousands of tiny burning Bibles under the ground. But he can, apparently.

‘Can you?’ I ask.

He sweeps his arm around the damp vista of Courtenay Place—the glistening footpath, the bus shelters with their huddled masses in outdoorsy gear, the pristine new toilets whose chic neo-modernist aesthetic reminds me of my newly famous home, the massive Transformer-like monument to New Zealand’s film industry down the far end that Sandy ‘loathes’ and Vero has on her ‘must-see’ cultural hot-spots schedule, the welcoming lights of the mini-mart, the strip joint a few doors up from which comes a weary morning-after subwoofer bass thud. I’m guessing his gesture means yes, they’re all over the place, all under the place.

And considered from another perspective I’m tempted to say yes, I can too, now that you mention it. I can hear the tiny burning Bibles under there. After all, the dude wasn’t asking if there could be thousands of tiny burning Bibles under the ground, only if I could hear them (if they were there). And if by thousands of tiny burning Bibles I’m to understand doubt, that accelerant to the incineration of rational belief, then yes. Yes, I can hear that sound—indeed I’m standing outside the very temple of doubt as we speak. And Nancy’s words come back to mind: ‘Believed. What does she think she is, a Catholic?’

My path is lit by them, the burning Bibles.

‘Thanks, dude,’ I say, and give him the whole packet. He’s lucky but he’s just made me luckier.