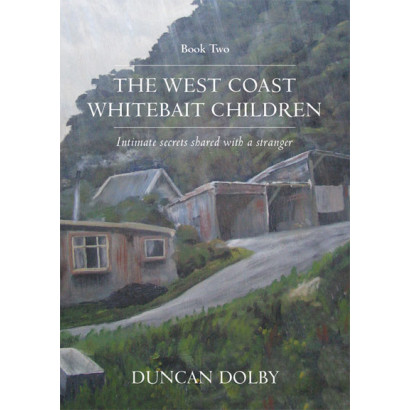

The West Coast Whitebait Children - Book 2

Intimate secrets shared with a stranger

Books One and Two are part of a series. They are based on the intimate and vivid depiction of the lives and legends of characters, places and events from the South Island over the past sixty or so years, particularly on the West Coast. They are about the complexities of growing up, youthful and elderly romance, lost and fulfilled aspirations, and delicious revenge. Stories include humour, and insights into the spirit of the Coast: about its beauty, ancient Maori and recent history, village life and people, and the importance and demise of coal mining. Our ‘whitebait children’s’ love of whitebaiting, though compelling for them, is just a glue that helps link memorable characters, places and times. The reader will come to like Millie, admire Molly and George, and love the wonderful long-deceased Lettie who ‘saw’ more in her short life than most of us ever will. And she was blind.

From: The West Coast Whitebait Children - Book 2, by Duncan Dolby

CHAPTER ONE

AT THE MAHITAHI RIVER MOUTH

The young dark haired boy was busy getting ready with his whitebait net at the mouth of the most-times beautiful and sometimes threatening Mahitahi River at Bruce Bay, South Westland. It was a Wednesday morning: warm, the air still and the sky an azure blue. There had been a little rain in the mountains but the river had remained low and clear. Several lazy white-topped waves could be seen from the road at any one time. The incoming-tide was two hours old and the waves pushing over the sandbank were, yet, too small for the shoals of whitebait to run up the river.

About eighty metres upstream from the boy were a dozen men and women who were readying themselves along the east bank. Most had come for this one incoming tide. They stood or sat on large rocks that had been carefully placed to help withstand the destructive whims of the river and the frequently violent seas. Where they stood, a lagoon and a seventy metre-wide scrub-covered sandbank had once seemed permanent parts of the river landscape just a year before. Now the only major coast road was at risk as well.

Locals knew only too well of the potential for rapid change at the river mouth. A year previous, a German tourist couple had parked their Volkswagen car close the sea edge of the carpark, only to escape in the night to see the car washed away by huge waves.

The men and women closest to the boy regularly glanced towards him and the incoming sea, and mused. They had time to waste and to speculate. The boy seemed too young to be there. The waves had not arrived at their positions but the boy had started to scoop through the shallow waves that rolled onto the beach beside where he stood. The whitebait would not be long.

Soon, the boy seemed to be having success. The observers saw him scurry up the bank and empty his net into a red bucket. He was also throwing unwanted things away, almost certainly twigs and leaves that tended to plague the shallow waves where he stood. The observers felt that they had chosen their own positions well, away from the debris. The boy’s position would soon become untenable because of the increasing size of the waves. The men and women furthest away decided that the boy was probably inexperienced, surely catching mostly sprats, smelly cucumber fish or useless flotsam. The closer ones saw that the boy looked assured as if he knew exactly what he was doing.

As the waves grew, the boy moved closer to his observers, his analysers. They could see that he should have been at school, probably wagging to earn some pocket money. One man internalised that wagging was a bad thing to do, as both illegal and wasting of educational opportunities. Another, less virtuous, thought wagging would be okay if the boy caught lots of whitebait; and especially if ‘the boy had a very boring or sour-faced teacher, or no friends at school’. He could recall boring and unhappy school days twenty years previous, or a time when school didn’t seem to be the best option. Another man, by himself, thought that the boy’s wagging was similar to his own taking of ‘a sicky’ for the day. As for the boy’s view of his own real situation, his school probably wasn’t the best option for that day, that week or even the entire year.

The boy had his own analysis. He kept at a distance from the adults to help forestall their inquisitiveness, or any challenges they might raise to his being there. They might otherwise ask about his parents and what they thought about him being there, if anything. They might speculate that his dad was hard at work conscientiously supporting his precious offspring’s future. His mum might think he’d gone to school. Perhaps they’d ask if his mum had made him hearty sandwiches and ironed his shirt. And, how would he, the boy, explain having fresh whitebait when he got home, or the money he had made. Worse still, how would he manage getting told off by the grouchy principal or teacher for missing class? The potential inquisitors might then question his audacity and the worthiness of his bold business venture, if it was. And, was the venture going to be worth it?

One elderly woman who had walked towards the river mouth noticed that the boy looked Maori. Though the boy was young, he might be exercising some tangata whenua rights or concession to fish, like some Southland children do when they catch mutton birds on the Ti Ti (or Muttonbird) Islands each year. Those children take time off school, though it’s well known that some of them use the oily and salty birds as an excuse to wag school. As for whanau rights to whitebait, the woman had not heard of those, nor were they mentioned in the regulations that were nailed to the post near the road.

CHAPTER TWO

THE MAN

Two hours after the boy had caught his first whitebait, a smartly dressed man in his late forties arrived at the river mouth to buy whitebait. Most of the day-trippers said that they wouldn’t sell their catch, or didn’t have any to spare.

The man was in no hurry to return to his sparsely equipped motel, or to his public service briefcase full of tiresome concerns and complaints. Back in his office, he preferred to file the letters that came to his office, or defer them to the future, usually minimising them to his secretary as ‘mostly petty and trivial requests from the electorate’. With little hesitation, he’d given his paperwork a rest for the day and headed to the river mouth. It was also helpful that his cellphone was out of signal-range at the river and that his secretary would not be able to contact him. He had done the same on previous occasions as well.

The self-assured man had bought sandwiches, biscuits and two bottles of soft drink from a distant garage to tide him through the morning. It was sunny and he was happy to watch, at least for a while. His wife was at home in Wellington and his teenage son would be at school, as expected. As far as he was concerned, he was alone, except for the preoccupied strangers on the bank. Likely as not, nobody there would recognise him, or even care about his presence. Perhaps, he thought, he should have warn more casual dress.

At first the man watched the adult whitebaiters as they tried and tried again, mostly from dry and safe ledges above the growing and incoming waves. He decided that they must be unemployed or unemployable, retired, or plain wagging from their work. Even the women could be those, though some could be trying to supplement their household income or larder, or both. None of the adults were having much success.

Then the man noticed the boy. The boy regularly trod in and out of the surf, before emptying something into his red bucket. The man’s experience told him that the boy was of primary school-age. While it might seem ‘inappropriate’ for the boy to be fishing at that time of the day and week, the man still decided that he would ask the boy if he had some whitebait to sell. He then decided not to risk getting his own feet wet by going too close. He would wait until the boy had stopped whitebaiting for the day. ‘Then,’ the man thought, ‘I can offer the boy some money for his catch.’

With his mind set, the man moved closer to the boy and sat down on the remains of a large ancient rata log. From his vantage point, he watched the tide come in, and that the boy didn’t seem to eat or drink. He could see that the boy’s face alternated from gleeful smiles to serious concentration and anticipation. He also noticed that no one came even close to speak to him. None of the adults upstream seemed to have any relationship to the boy, other than by sharing a task. That situation caused him to worry, just a little.

Looking inland from the boy, the man half expected to see a patient and loving dog beyond the beach, like a Tom Sawyer might. But he could not see or hear a dog, nor did he detect the boy glancing up as if to acknowledge one. A more distant glance to the carpark suggested also that the boy’s transport might be a red Toyota utility, perhaps driven there illegally by the boy himself. The utility was parked well away from the other cars; and, seemingly, well apart from the prying eyes of the adults. The man speculated that the utility probably belonged to the boy’s dad, thus available to the boy through the father’s mindless loan, or borrowed as part of some boyish (but criminal) act of stealth and cunning. Either way, the boy was too young to drive.

After a further two hours, as the tide became full, even ready to turn, the man noticed that the other whitebaiters further up the bank were packing up. The boy’s behaviour also changed. He had become less purposeful, as if deciding whether to continue to trawl the waves, or not. The man decided that it was time to approach the boy.

At that time, the man also realised that he was not only interested in buying the boy’s whitebait, he was also intensely curious about the boy himself and his story. He also realised that he had more than his wallet to barter with. That’s when he picked up his bag of melted chocolate-coated biscuits, his one unopened bottle of soft drink, and walked towards the boy to see what he could learn, or buy.