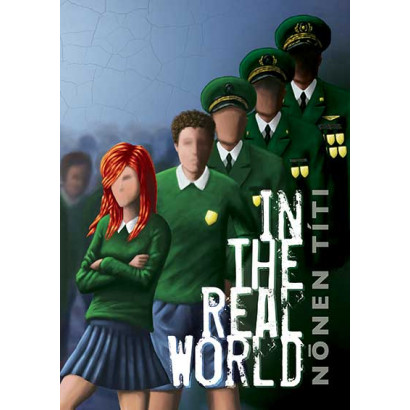

In the Real World

When trying to make sense of real world issues like war and human rights, two teenagers discover the roots of these problems when they find themselves in conflict with their school about obedience and uniforms. The book tackles themes concerning the rights of individuals and takes a strong stance against war.

It starts on Anzac Day, but the story applies to any memorial day and any war, since it deals not with the actions of war but with the emotions of it - the emotions that exist in all people.

From: In the Real World, by Nonen Titi

MARIETTE

I can’t remember not visiting the Paterson homestead on Anzac Day weekend. That four-day reunion is sacred to our family. Dad grew up on the farm, together with two sisters and six cousins, and all of them still gather there once a year.

I envy him having all those siblings and I would have preferred the empty fields over the stinking city. Or maybe not the city itself, but we’re stuck in a suburb full of snobs; dead forgotten, even by the public transport on Sundays.

Anyway, the reunions make up for it. Everybody brings food and drinks, there is music and dancing in the barn, games to play and storytelling, while TV, radio, newspapers, phones and computers are strictly forbidden. Grandpa Will confiscated three phones last year; one was Aunt Ellie’s.

For me, by far the best time comes with the sleepovers in the garden. There just aren’t enough rooms inside for all the Patersons – though nobody goes by that last name anymore – so only the toddlers sleep with their parents. Mum and Dad camp out in the summer room with eight aunts and uncles, while Miranda and my younger cousins share the attic. But we’re the lucky ones – Gabi, Jacqui, Lizette and I – because we get one of the tents, as do the four oldest boys.

Last year we told ghost stories until two in the morning when the boys scared us out of out wits with flashlight shadows and sound recordings. Of course, we had our revenge the next night when we filled their tent with dried leaves and grass. They retaliated with plastic-glove water balloons until we took refuge in the tool shed and then found ourselves locked in there for the rest of the night.

The battle lasted the entire four days with flour balloon and ice cube exchanges. The girls – of course – won the war. We managed to push the garden hose into their tent zipper and turn it on full blast when the boys were sleeping. I can still hear the squeals.

That’s why I’m now packing about a billion changes of clothes. I’m going to sleep with my gumboots on. My books are wrapped in two layers of plastic and I have a waterproof cover for my sleeping bag. I can’t wait until we get there.

JEROME

It seems that we’re the last ones to arrive, after having finally left late this morning. Dad drove way too fast, as usual. Rowan was carsick most of the way and I’m sure he’s as relieved as I am to be able to get out.

Over near the house the relatives are busy talking. The barbecue is burning and the music that’s blasting from the barn speakers can probably be heard in the village two kilometres away. The smell is familiar and reminds me of cow patties. A bouncy castle is dancing on air at the side of the barn for the youngest children, but even Rowan, at twelve, still likes those things.

To the hellos, and the “My, my, Jerome, haven’t you grown?”, and “Did you hear from your mum this Christmas?” questions I just smile and say yes. The various aunts and uncles then turn their attention to Dad, who is the youngest of the nine farm children. I’m sure he’ll wallow in their attention. Good, that’ll give me space to find my cousins and prepare for tonight. The cease-fire will be at an end and this time victory will be ours.

If Toine didn’t murder his older sister, as he said he would after the deluge last year, I’m sure he’ll be ready. No doubt Stuart and Glen are also in. But first I’m going to say hello to Grandpa Will. He’s my real grandfather and the youngest of all the ‘grans’, as we used to call them when there were still five of them. He’s only sixty-nine, but I don’t think he looks it and he often acts like a boy. That’s what Granannie says. I’ve got to get him on our side this time, because I’m pretty sure he was responsible for the flour balloons.

Whatever we do, we’ll have to find a weapon better than water to defeat the girls with.

MARIETTE

I find my gran in the kitchen lifting a tray of cookies from the oven. “Just in time, Mariette; I need a tester,” she greets me.

I carefully bite a piece off, trying not to burn my lips and nod approvingly.

“You’d tell me they’re good even if they were made of wax,” she says.

I give her a hug. “How are you, Granannie? You’re looking younger every day.”

She’s actually nearly eighty, but still kicking hard. “Stubborn as shit,” Grandpa Will says. She insists on doing her own cooking and only after her sister died two years ago did she agree to get a washing machine. Dad calls her an old hag sometimes – in good fun of course – and she’s my favourite.

I help her make a carafe of lemonade and carry it out to the patio where Grandpa Will is already in the middle of a story for the younger kids. He loves to repeat the tales of how our parents got in trouble when young and we kids love to hear that.

When Grand-maman and Grandpa Glenn were still alive we also had recollections from their childhood, but Granannie doesn’t tell stories. A dark shadow travels over her face when I ask about when she was my age. They lost three brothers during that time; one of them was her twin. She doesn’t want to be reminded. “I have it all written down. Once I’m gone, you can read it,” she tells us. But when Grandpa Will recalls the others times, she sits by with a smile around her wrinkled mouth and her eyes get that faraway look that always makes me want to travel with her.

This time I put the lemonade on the table and go in search of my companions, so we can get started making our tent boy-proof. This assumption slaps me in the face when Jacqui and Gabriela, being two and three years older than Lizette and I, tell us that they’re not interested in a repeat of last year’s ‘childish games’.

“Jacqui had a fight with Stuart on the way over. They’re not speaking”, Lizette says about our twin cousins.

“That should be more of a reason to get protection from boy-attacks. I’m sure Stuart won’t give up on the idea of getting revenge.”

“Apparently Gabi’s arranged with Grandpa Will to have the water turned off for the night, but we don’t really need water for a night-time war, do we?” Lizette waves her hand at the barn.

“So it’ll be just the two of us against four boys?”

“They might have the numbers, but we have the brains,” Lizette answers. “Unless you want to invite the younger kids?”

I consider that. Lizette’s brother is fourteen and pretty tough. Rowan can also hold his own, but Gabi’s younger sister is kind of reserved and Miranda, though a darling, is only eleven and can’t keep a secret. At any rate we’d still be outnumbered.

“I reckon we can handle the four of them alone, but we’ll have a fight, if only to teach those old women that we won’t be talked down on,” I tell Lizette.

We retreat to the kitchen to collect our thoughts. “We’ll have to be clever about it; a guerrilla war. They often win because they battle with sneak attacks, not proper war rules,” Lizette says.

“Wars have rules? How can you have rules about killing people?”

“Sort of. We had a pretend war at our school for civics. Each of us had to play a role.”

“Cool. So far for civics we had some boring lectures about equality and democracy,” I say.

“What are you girls up to?” Granannie asks, coming in with a plateful of cake slices.

“Secret warfare,” Lizette tells her.

JEROME

My hopes are not disappointed. Stuart is especially keen on the battle and he’s usually the leader of our foursome, being the oldest. Glen and Toine are just as eager, seeing their camera and CD-player were ruined along with my diary last year.

“That’s why we won’t have a water ballet this time,” Grandpa Will tells us when we ask why he’s switching off the supply. “I have no problem with you kids having some fun, but it has to be exactly that: Fun.”

“Of course we don’t need the taps. There’s a whole dam out there,” Glen says when we wait in the tent for the lights in the big house to be dimmed.

We’ve pitched our tent near the tool shed to keep the girls from having access to its contents. They’re uphill near the barn. The dam is below us, much nearer than they would like.

“No water tonight. That’ll be our final move. I have a better idea,” Stuart says and waves for us to follow him.

In the tool shed is a huge vessel filled with worms – part of Grandpa Will’s fishing supplies, though most go onto the compost heap. We fill a bucket with the wriggling mass and make our way uphill. “I can’t wait for the screaming,” Glen says.

“Shh.” Stuart uses two hands to try and open the zipper of the girls’ tent, but even then it won’t budge.

“Who’s there?” asks Jacqui’s voice from inside.

“Damn, let’s go.” Stuart motions to the back of the barn where we can watch from.

A light inside shows two silhouettes struggling with the zipper. They can’t open it either.

“Even better, we’ll help them a little,” Toine suggests.

With the girls gathered at the front it’s quite easy to help the tent topple over. Cursing and yelling from inside sends us running back downhill. I crash into Toine when he suddenly comes to a stop. “Our stuff!” he cries, pointing.

The tent is gone, or rather, it’s floating on the dam. Our things have been dumped on the bank and the mattresses deflated. “Bitches,” Glen groans. “Now what?”

“We’ll get the worms and fill their sleeping bags with them.”

We never get that far. The moment we leave the tool shed after putting our things there, we are met by Uncle Rory and four furious girls.

“What is this about you boys sewing their tent shut?” Uncle Rory asks.

“We did not!”

“Well, it wasn’t done by elves.”

“Our tent is on the dam. That wasn’t elves either,” Stuart says.

“We never did that!” Jacqui shouts at him.

Uncle Rory doesn’t wait for more explanations. “I don’t care who did what. I’m going back to bed, but those tents had better be fixed and dry by morning.”

“Let’s go,” Toine whispers.

I follow them, relieved that Uncle Rory doesn’t remember his threat from last year to have us separated and supervised at night. We take some long rods and hooks to the water’s edge to try and retrieve the tent. In the meantime the thickening fog is making my clothes wet and my hands so cold I drop the rake twice.

After a while, Stuart throws down his hoe. “This is dangerous. We can’t even see where the bank ends. We’ll wait until it lifts.”

“My dad will come and check in the morning,” Toine warns him.

“I’d rather risk trouble with your dad than one of us drowning. Let’s go inside.”

“Oh no,” Glen says, again coming to a halt, “we forgot the worms.”

We climb the hill again, but the bucket isn’t where we left it. Too aware that we might find our own sleeping bags filled, we return to the shed, but nobody’s touched our stuff. We sit around, cold and unable to sleep, speculating on when and how it happened until the early light starts showing the outline of the dam and we can rescue our tent.

MARIETTE

“Oh bless you, we’re so lucky. This has to be an omen. The great oracle is telling us we’re sure to win this war,” Lizette proclaims when we find the bucket behind the barn. “Breakfast anyone?”

We tiptoe through the kitchen of the house to get to the staircase down to the cellar, where we hide both the bucket and the contents of our bags for safekeeping. We spend the last hour before dawn in the barn wrapped in horse blankets – there’s all kind of interesting stuff here even though the horses have long gone – and by the time it’s fully light act two is written and approved.

It turns out to be a little difficult to go anywhere unseen during the day. The boys, after having searched in vain for their precious worms, watch us like hawks. Gabi and Jacqui do nothing but bitch about having to fix the tent and the whole family is informed about the mishaps. Our break comes when they all gather in the summer room to watch the video Aunt Ellie made of last year’s reunion.

We don’t wait long that night. Lizette is the first to scream really loud when she ‘discovers’ the worms in her bag. Jacqui soon does the same and then swears she’ll kill her brother. No doubt Gabi would like to do the same to Toine, but she satisfies herself by striding to their tent – with us behind her – and slapping him in the face. The looks the boys send us are worth every minute of lost sleep. Nobody summons the adults this time.

Jacqui and Gabi spend the entire night trying to free their clothes of worms with the accompanying shrieks of disgust while Lizette and I just take our bags out of the tent. The boys might be plotting a counterattack, but they don’t make a move that night, probably because they know we’re all awake. I’m having as good a time as last year, if not better. Lizette is the best ally I could wish for and we still have twenty-four hours left.

In the morning the adults are informed once again and the boys end up being told off for the worms, the evidence of which was discovered, to their own surprise, just inside their tent. Jacqui and Gabi spend hours washing their clothes while Lizette and I make this a pyjama day, adamant that our possessions were stolen from the bags when the boys deposited the worms.

JEROME

“Isn’t it fishy they seem to come out clean every time? Jacqui and Gabi get locked in the tent and worms in their clothes and we get blamed.”

“And the adults believe their innocent faces. You’re right, Jerome. Our sisters are as much victims as we are,” Stuart agrees.

“I don’t care. Gabi deserves payback for that slap,” Toine says.

“Maybe later. For now we concentrate on the other two. This is our last chance and they have it coming. I bet it was them last year as well,” Glen replies.

“No more games. This is it. We have to teach them tonight or we’ll never hear the end of it in this family; those stories will be told for years to come. Never mind what Jacqui tells the girls at home,” Stuart agrees.

“How the girls outsmarted the boys? I say never, right Jerome?” Glen asks, punching Toine on the arm.

“Right. We deserve a bit of justice. We’ve been falsely accused,” I answer.

“And we’ve been unjustly made to fix and dry our tent and pick worms.”

“And we’ve almost caught a cold in that fog,” Toine adds.

“And we didn’t get any sleep at all.”

“And Gabi hit me because of them.”

“This is turning into a labour camp for us.”

“That’s true. We can’t let them. We didn’t start this and they keep attacking us.”

“I bet you they’re planning to sink our stuff. The tent was only a warning.”

“Right, because they can’t get to the hose they’re taking it out on us.”

“That’s girls for you. They play mean. They ruin our things and they’ll stand by laughing when we dive to the bottom of the dam to retrieve them.”

“And of course they’ll go into tears when asked, so we get the blame on top of it and we didn’t do anything!”

“They’re born evil, I tell you. Girls can’t think fair; they’re hormonal.”

“We need to protect ourselves. Make sure they can’t get to us.”

“Yeah; if we wait any longer they’ll attack and it’ll be too late for our things.”

“Let’s make a stand; the four buccaneers,” Glen says, getting to his feet.

“Crusaders for justice for the male gender,” Stuart adds.

“Avengers of abuse,” Toine agrees.

Next they all look at me. “We rise as one against the woe of man?”

“What?” Glen asks.

“The woe of man, woe-man, woman.”

“Oh, I get it. That’s good. We’ll drink to that.” Glen raises his can of Coke and we all join him.

MARIETTE

It’s a lot of fun to have an excuse not to get dressed all day. The boys call us ‘pyjama kids’ and we respond with demands for our missing clothing for which they have searched high and low. Not just them, but the adults as well. Uncle Alistair even interrogates the boys since his family will leave early morning. “Lizette needs to pack tonight,” he says, but our things stay lost.

The younger boys, Marc and Rowan, have been employed, eager for a part in the war, but nobody thinks of looking inside the empty barrel. Lizette and I lounge around the kitchen and listen to stories. Granannie spoils us a little extra. She knows just fine what’s going on. What she doesn’t know is that the tree behind the tool shed is decorated with the boys’ underwear, which will be in plain view once the motion-detector light goes on, which it always does when the boys walk downhill. No doubt they’ve already got an attack on our tent planned, so they’ll be more eager and less cautious about where they step. All we need is for one of them to move slightly toward the side of the tent and trip over the wire Lizette connected to a remote control, which in turn will switch on the power to the cassette player that’s attached to the sound system inside the barn and the speakers. The entire farm will be treated to a conversation between our tent buddies about boys in general and their brothers in particular. To top it off we’ll distribute some lovely printouts made from old photographs, featuring Glen in nappies, Jerome puddle naked in the bath, Stuart equally so and covered in paint and Toine on a potty. These baby bodies, however, have their current heads attached.

First on the distribution list are the attic rooms, since Miranda and Bettany won’t need encouraging to show them around. We leave some in the photo albums, but the last four we carry with us to put in the barn for Jacqui and Gabi to find when they run in to switch the tape back off.

“I wish we could see their faces,” I whisper when we carefully avoid the hidden cassette player next to the barn door.

“We’ll be lucky if we can see anything from here. Look at that fog coming in,” Lizette answers, reaching for the handle.

The moment I step inside something thick pulls me backward. A muffled sound alerts me to Lizette falling to the floor before my vision gets blocked by what smells and feels like a blanket over my head. I try to yell, but my mouth is filled with fluff. I try to kick against the weight of the person pinning me down but without success. Next something pulls my ankles together so tight it hurts my skin and then my hands.

I know it’s the boys; it has to be and I shouldn’t give them any pleasure out of this. Trying to stay calm I wait for them to start accusing us, but they’re not speaking. All I can hear is shuffling and the occasional moan from what must be Lizette. I can’t see or speak, nor walk or defend myself when they pull me to my feet. Suddenly I’m lifted off the ground, unable to stop them. I’m helpless and it makes me furious. I’m jolted one way and the other. They must be climbing over stuff. Where to? I feel so stupid, so out of control. This can’t be. This isn’t funny and why don’t they say something?

…What if it isn’t the boys? Where’s Lizette? I don’t want this. I pull my knees up and jerk as hard as I can.

“Ouch, damn,” I hear as my legs drop down followed by a loud clattering noise that frightens the life out of me. There’s a stifled giggle: It is the boys.

I can’t keep them from picking up my legs again, though I fight and kick as good as I can. Eventually I end up being dumped face down on top of something hard and round – a saddle. How stupid! I force my mind away from the image but the questions come anyway. What are they up to? Their silence and calm spooks me. I just want to get out of here.